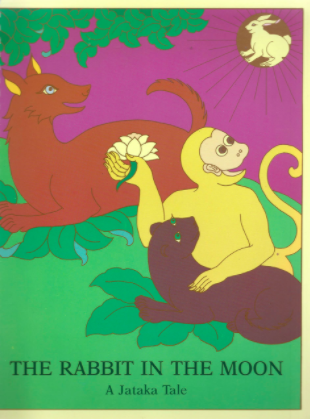

The Rabbit in the Moon

Book Module Navigation

Summary

The Rabbit in the Moon considers questions of friendship, courage, and altruism.

A generous rabbit gives up his most precious possession for a lost traveler and is lifted to the heavens where his generosity continues to shine for all time.

Guidelines for Philosophical Discussion

There are several philosophical issues in the book, The Rabbit in the Moon–friendship, change, and courage–but the most prominent theme is the power of goodness, kindness, and altruism. The book gives a simple message that being good and kind is exceptionally valued. In fact, the story goes to the extreme by presenting the heroic self-sacrifice of the rabbit as something highly rewarded. In the third part of the discussion questions, children are asked to think about this message and to question it. Starting with more specific questions, such as whether they have been altruistic, discussing what it means to be altruistic allows children to grasp the concept so that they can talk about it more abstractly (e.g. is it right or wrong to be selfless and to self-sacrifice, etc.). These questions are open and are designed to give children an opportunity to think about who they are and what their rank orders are regarding selfishness and selflessness, as well as to reflect on other people’s opinions, and possibly adjust or change their own as a result of new information and ideas. In this discussion, through carefully raising open-ended questions, a facilitator is gently guiding the children into discoveries that might be contradictory to what they’ve known. For example, if children all agree that being selfish is bad, which is possible considering that in everyday speech this word has derogatory connotation, the facilitator could come up with an example that would question that opinion and therefore make children realize on their own that being selfish could be–and is–good at times. Or perhaps, some children might question the example and show valid arguments against it, which would make room for deeper discussion and thus deeper understandings.

In this discussion children might be faced for the first time in their lives with questions about when it is acceptable to be selfish, when to consider being selfless, and when (if ever) to risk your life for someone else, etc. Aside from teaching them to think and find the answers to hard questions, this ethical discussion about altruism is also useful in preparing them for possible conflicting situations in their lives–situations where it is necessary to decide on limits of their own selfishness (or selflessness), for example.

Ethics and social philosophy issues are intertwined in the discussion on friendship: the questions are designed to spark a conversation about the meaning of a good friendship and the ways in which we all influence each other. Starting from their own experience, children can define characteristics of a good friend and possibly prioritize some characteristics over others if asked to. For example, they could be asked, “Would you rather have a friend who is loyal or one who is smart?” This would then open up the separator issue of rating virtues. It is important to mention that this particular question set, just as all the others, is just a general frame. Thus, apart from answering these pre-made questions, the discussion itself might lead to more questions such as: Just because someone is our friend, does it mean that this person is always good for/to us? Can someone be a bad person and still be a good friend? What makes someone a bad person? It’s also possible that many of the pre-made questions are not answered or even asked, because the discussion takes a different course. The facilitator’s job here is to be open and flexible, to actively listen to the children, and to recognize interesting ideas that could be worth exploring further.

The second set of questions encourages a direct ethical inquiry into the virtues of courage, fear, love, and how they relate. This discussion (as well as the other two) presents a problem of conflicting qualities existing together–just because someone is being brave does not mean that they didn’t experience fear just a moment ago or perhaps is still feeling fear while working against it by being brave. Again, examples are presented as open-ended questions (e.g., What if X happened?) that will expose children to such ambivalent possibilities and could help induce children to think about the world in terms of shades of gray rather than black and white. Also, although the issue of love is raised in questions only in a relation to fear (as a reference to the book’s lines that connect the two), the discussion might continue on, if appropriate, to ask what is love, how do we know that we love someone, or how do we know that we are loved.

The philosophical issues raised in the question sets–friendship, courage, fear, love, and altruism–are the essential part of our lives. Therefore, children will be happy to discuss them and will probably have a lot to say. In addition, with the community of inquiry they will learn actively by reflecting on their own thoughts and the thoughts of their peers–rather than passively as when reading a book or listening to a teacher. Finally, even if there is no one clear conclusion that the children can take away with them at the end of the discussion, they will still learn a lot about the concepts that were discussed. More importantly, they will learn how to stop and think, to question, and to consider different possibilities, explanations, and opinions.

Questions for Philosophical Discussion

Friendship

“Though he was not as strong as the elephant nor as bold as the lion, he possessed the kindest of hearts.”

- How would you describe the rabbit?

- How was he a friend?

- What did he do to show he was a friend?

- What does it mean to be a good friend?

- What kind of things do you do as a good friend?

- What are some of the attributes that your good friends have?

- What are the important qualities that make one a good friend?

- Can friends make you change? Do you become different as a person because of who you spend your time with? Why/Why not?

- If friends could make you change, would that be a positive or negative thing?

Courage

“Feeling only love for others, he had never been afraid for himself.” (or) “And he leaped toward the blazing fire.”

- Is the rabbit in the book brave?

- Why was or wasn’t he brave?

- What does it mean to be brave?

- How do you know that you are being brave?

- The rabbit in the book jumped into an open fire. Do you have to do something really dangerous in order to be brave?

- Can you be afraid and brave at the same time? Why/why not?

“Feeling only love for others, he had never been afraid for himself.”

- Did you have any experiences where love made you feel fearless?

- Can love help you feel less afraid?

Altruism

“Then in order to remind the world of the power of selflessness, he placed the rabbit in the moon, where he has dwelt from that day forward.”

- What is selflessness?

- Have you ever been selfless?

- How can you tell that you are being selfless?

- Is being selfless good or bad?

- Is it always good/bad?

- The Rabbit was so selfless as to give his life to a stranger. Do you think that was the right thing to do? Why?

- Would you do something that would help other(s) but hurt you? Why or why not?

- Do you think the king of heavenly beings was right or wrong to put the rabbit in the moon?

Original questions and guidelines for philosophical discussion by Jelena Spasojevic. Edited June 2020 by The Janet Prindle Institute for Ethics.

Find tips for leading a philosophical discussion on our Resources page.