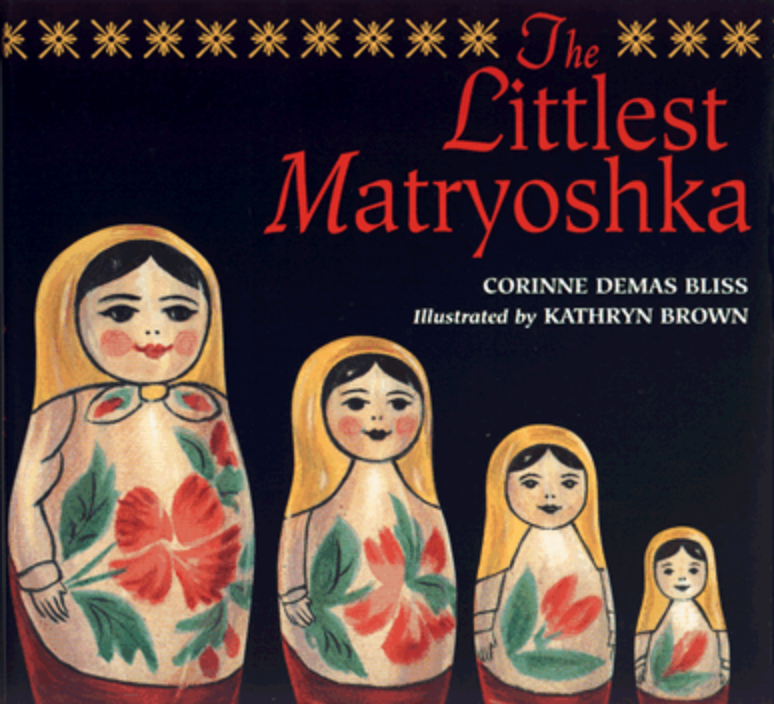

The Littlest Matryoshka

Book Module Navigation

Summary

The Littlest Matryoshka prompts a number of questions about philosophy of mind, essence, and consciousness.

The journey begins in a Russian village, where six special sisters are made out of wood—they are nested dolls. So these Matryoshka sisters travel far, seeking a home in America. The biggest sister, Anna, is made to keep them safe, but Nina, the smallest sister, faces danger as her sisters are sold at a discount. Swept away, she finds scary situations, but her only comfort is remembering her sisters. How will Nina find them?

Read aloud video by Fiddlefox

Guidelines for Philosophical Discussion

The Littlest Matryoshka is a heartwarming tale full of adventure. The story is about sisterly love, hope, and discovery in the face of turmoil. What makes this story of unique philosophical interest is the fact that these “sisters” are nesting dolls made of wood. When leading a discussion on this book, the idea is to encourage the children to think about metaphysics and the philosophies of mind and language. Topics include whether or not a doll can have an essence, mind, or desire. In addition, issues concerning fate and design begin to unfold. The question becomes, “Do the Matryoshka sisters have the capacity to experience the themes of this book, including, sisterly love, hope, discovery, and turmoil, bearing in mind the philosophical implications of each?”

The question of whether or not a doll can have an essence arises from matters of consciousness and its states. Children often have a doll or dolls that they become attached to, nurture, name, and tell secrets to. This phenomenon is not restricted by gender. Action figures, stuffed animals, toys, blankets, and other objects take on these roles for children. Asking the children about these things will lead to an interesting discussion because they can relate to the concept of a doll or another object having human qualities, or at least treating them as if they do.

In the story, the sisters seem to be aware of what’s going on. They seem to be made aware of themselves and each other, as well as their surroundings, when the toymaker named them and told them they were sisters. Can these wooden figures possess some type of consciousness? How we can know this only will be answered when we decide what is necessary and sufficient for consciousness. This question is debatable. The students can talk about whether or not they believe the sisters actually are aware of what is happening, and how they can tell one way or another. From the issues of awareness/consciousness arises the mind/brain problem. The children will discuss whether or not the brain and mind are the same by thinking about if there is a difference between what people mean when they say things like “use your brain” or “think with your heart”, and if you ever have to decide between the two. The issue then becomes a question of whether or not Nina and her sisters actually felt or thought anything at all and how or if they can know with certainty.

The subjects of desire and design can be addressed in two ways. Two sisters, in particular, deal with the issue. Anna, the biggest sister, is charged with the safety of her smaller sisters. To protect, however, implies an act of volition that requires intention. Intention reflects a desire. At times, people can have the desire to protect but not the means. Perhaps Anna has no capacity to desire at all; alternately, perhaps she has the desire but not the means. In the end, Anna’s sisters are “safe” with her. The students can decide if they think she did her job. An example can be given of parents, who have the job of protecting their kids and keeping them safe, yet parents can’t be there all the time. The students may connect Anna’s experience to this idea. This end result reflects the goal of Anna’s charge, but is this the result of her desire to perform her duty? The students will talk about why or why not, and if Anna can want to protect her sisters. The capacity of Anna to desire will lead to questions about design and predetermination. Was it fate that Anna and her sisters were purchased by the girl who Nina “found”? Was it a coincidence?

The second approach to desire and design in this story occurs through Nina’s experience. At the end of the story, after having endured forces of nature and encounters with animals, Nina is reunited with her sisters. Jessie, the girl who bought Nina’s sisters at a discount, places Nina with the others, who states, “Oh, you found us!” The students will discuss whether or not Nina actually “found” them. Finding, like protecting, implies volition. It is clear that one object may be found in the course of looking for another. In this sense, it is not required that one look for an object in particular to find it. The children will decide whether or not Nina was looking for her sisters, and, in either case, if she first had the desire to find her sisters, then if she had the capacity to find them. They will discuss what is required to find and if Nina meets those requirements. When asked, students may decide other characters in the book better meet these requirements. A chart may be done to compare characters and match their experiences in the story to the decided requirements for “finding”. They may discover that they disagree with the book. Perhaps Jessie found Nina. It may be interesting to see if the students think that this series of events, and Nina’s “finding” or reuniting with her sisters happened by accident (chance) or purpose (fate or design). By design, I mean whether these events happened for a reason and if they had to happen for Nina to be reunited with her sisters. Perhaps the Matryoshka sisters were destined to be together, or maybe it was a succession of accidents that lead them back to each other.

Questions for Philosophical Discussion

Essence and Consciousness

- How is Nina like a person?

- How is she different?

- Is Nina a person? How do you know?

- Is she more like a person or a doll? Why?

- What is Nina like? Does Nina have a character/personality?

Nicholai, the toymaker, said, “You are six sisters,” and gave each one a name. Then he sends them to find a home in America.

- Do Nina and her sisters really know that each other are there? Why or why not?

- Do they know they are sisters? Explain.

Philosophy of Mind

- How can you let someone know what you are thinking or feeling?

- If a person can’t let you know what they think or how they feel by doing the things listed, does that mean they can’t think or feel? Why or why not?

- If a person can’t hear, speak, or see, does that mean the person can’t think? Why or why not?

- How is that similar or different from the sisters in the story?

- What do you need to think?

- What does it mean when someone says, “Think with your heart,” or “follow your heart?”

- Is it different than when someone says, “Use your head!”? If so, what is the difference?

- Do people ever have to decide between thinking with their heart or thinking with their head?

- Is the mind the same thing as the brain?

- Could it be different?

Original questions and guidelines for philosophical discussion by Sarah Vazquez. Revised by Jayme Johnson. Edited June 2020 by The Janet Prindle Institute for Ethics.

Find tips for leading a philosophical discussion on our Resources page.