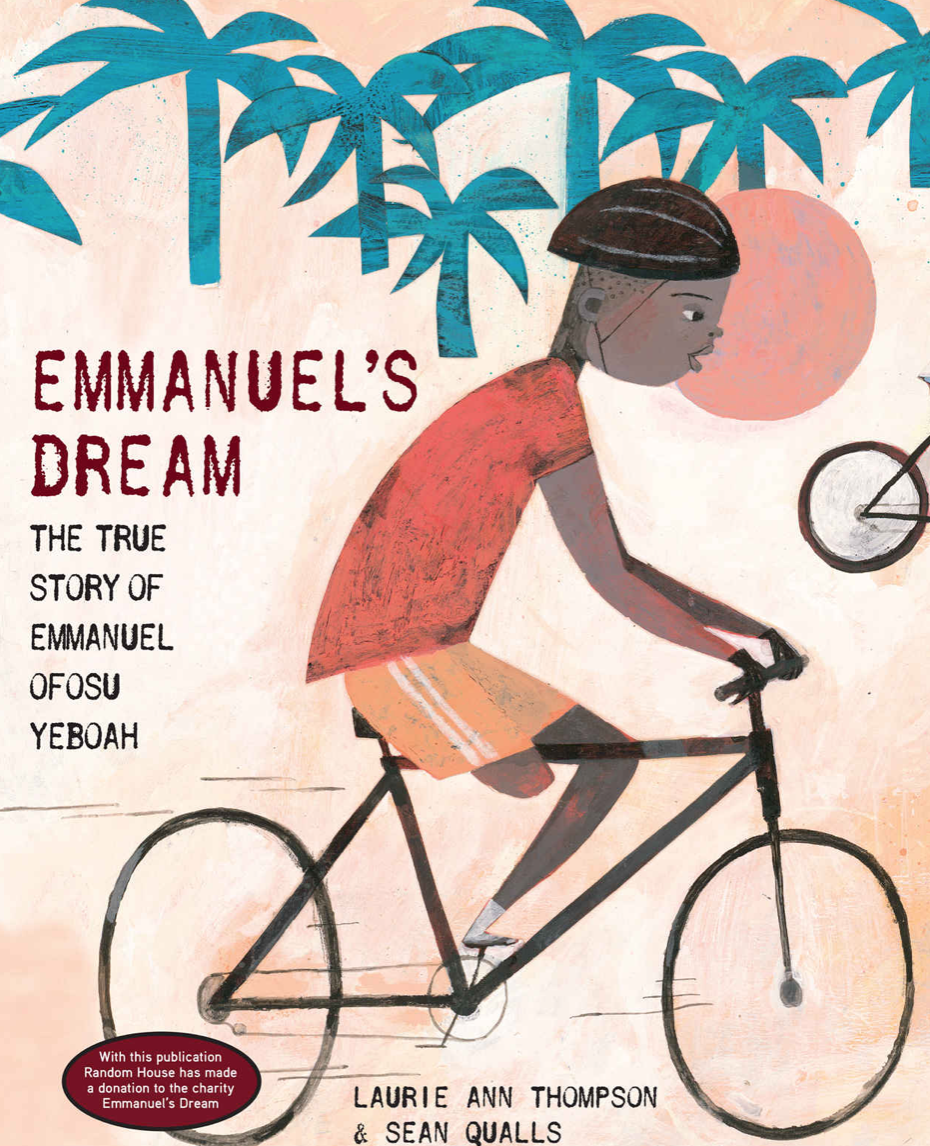

Emmanuel’s Dream

Book Module Navigation

Summary

Emmanuel’s Dream examines what it means to be disabled and allows for a discussion of different models of disability.

Emmanuel is born with one leg. However, his mother teaches Emmanuel not to let this physical impairment prevent him from doing things other kids do. When his mother passes away, Emmanuel decides to honor her by showing other people that “being disabled does not mean unable.” He bicycles around Ghana, inspiring those with and without physical challenges, proving that it is possible to accomplish something big with just one leg.

Read aloud video by Reading Rhinos

Guidelines for Philosophical Discussion

Baby Emmanuel is regarded as a curse in his community because he is missing a leg. People do not hesitate to label him as a disabled person. Here, you can pause for a moment to consider what counts as disability. At first glance, disability might seem to be about being abnormal; most people have two legs instead of one. It seems reasonable to assume that if everyone around Emmanuel had one leg, him having one leg would not cause a stir. Yet, what if a person in our society was missing an eyebrow (permanently), had never hiccuped, or only blinked three times a day? Would you label that person as disabled? The majority of people would intuitively answer no, even though such cases veer from the norm. These people might then argue that you must take functional inconvenience into account; missing a leg is likely to be an inconvenience while missing an eyebrow isn’t. What then, if you consider a person without a leg in a wheelchair and a person with terrible eyesight wearing glasses? Both of them are reliant on their tools to move around or see. They are also occasionally inconvenienced by their tools–a wheelchair getting stuck in a doorway or glasses fogging up in a warm room. Yet, even though most of us would consider the former as disabled, we probably wouldn’t with the latter.

Perhaps the issue here is one of sources of inconvenience. No reasonable person blames a pair of glasses for fogging up; it is merely following some law of physics. However, one might criticize society for failing to accommodate people in wheelchairs. If you lived in a society that accommodated the functional needs of disabled people (with slopes, wider doorways, or textual paving blocks for example), would there still be such thing as disability? This line of thought fits into what disability scholars and activists call the human variation model. According to the human variation model, disability is a set of physical or mental attributes that the current social institutions fail to accommodate.

Trying to explain disability with functional inconvenience raises other problems as well, like who gets to decide whether something is inconvenient or not and whether the inconvenience is simply functional or not. What if a person were blind, but did not feel particularly inconvenienced by it thanks to their highly-developed echolocation skills? Moreover, what if you had epilepsy, but the seizures were so mild and infrequent that you were hardly inconvenienced by it? Our intuition might still tell us that such people are disabled even if they are not actually suffering from functional inconvenience. This suggests that something else is at play here. First, our lack of understanding on what it is like to live with a disability makes us assume that disabled people necessarily suffer from inconvenience, promoting a stigmatization of disability. Next, it might still be reasonable to say a person with mild epilepsy still experiences inconvenience–not so much from functional one, but from discrimination. This view aligns with what disability scholars and activists call the minority group model. The minority group model views people with disabilities as a minority that suffer from stigmatization and discrimination along the same lines as racial or ethnic minorities.

So far we have looked at two models–the human variation model and the minority group model. Both of these models fall under the social model of disability. The social model views disability as something caused by an interaction between an individual and the social environment. The medical model, in contrast, views disability as something that results primarily from the impairment itself. This leads to a discussion about whether people with disabilities face challenges because of the way society treats them or because of the biological nature of their disabilities.

This could lead to a further discussion on the relationship between disability and well-being. Emmanuel does not seem bogged down by his physical impairment. In fact, he uses it to enrich his life. Can disabled people ever reach the same degree of well-being as non-disabled people? Or are they inevitably hindered from pursuing well-being because of their disability–even if society was accommodating of them?

Questions for Philosophical Discussion

Nature of Disability

- Is Emmanuel disabled? Why?

- Are disabled people not normal?

- Do you call a person disabled if they are not normal? (Use specific examples if necessary- missing an eyebrow, wearing glasses, etc.)

- Do you think people with disabilities lead difficult lives? Why do you think so?

- How can others make their lives easier? (Use specific examples if necessary–for a person in a wheelchair–build slopes, wider doorways, etc.)

- Do you think people with disabilities will still lead difficult lives even with those things (that might make lives of disabled people easier)?

Disability and Well-being

“In this world, we are not perfect. We can only do our best.”

- Can you think of something that is both good and bad?

- Is disability a bad thing?

- Can it ever be a good thing?

- Can you think of something that you like about yourself that you didn’t like at first? How did that change happen?

- What if you became blind or deaf or lost a leg? How would you feel at first? What would you do? Do you think there will be any change in how you feel about it after awhile? Do you think you can be happy again?

- Can people with disabilities live just as happily as abled people? Why or why not?

Original questions and guidelines for philosophical discussion by Rina Tanaka and Zachary Touqan. Edited June 2020 by The Janet Prindle Institute for Ethics.

Find tips for leading a philosophical discussion on our Resources page.