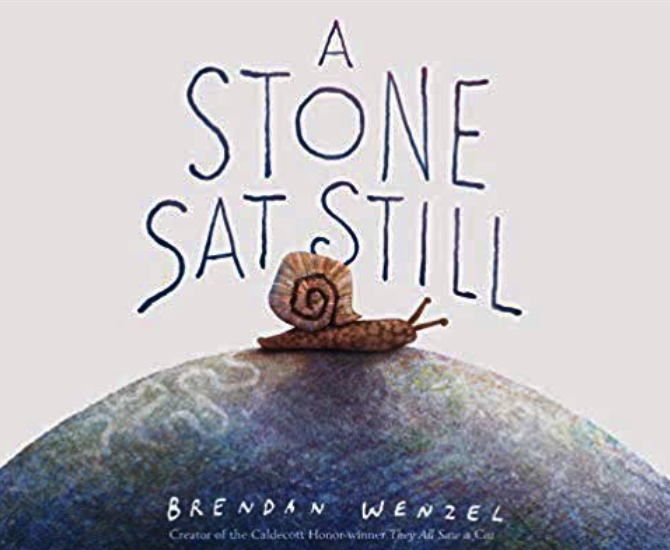

A Stone Sat Still

Book Module Navigation

Summary

A Stone Sat Still raises questions about objectivity, perception, change, and memory.

This is a story about a rock that seems ordinary and unassuming, but to the animals around it, it is so much more–a haven, a hill, and a quiet resting place. Each animal approaches the stone from a different place and gets something different from it. This story shows how, despite the stone not changing in composition, the surrounding environment and animals’ perspectives affect the stone’s appearance.

Guidelines for Philosophical Discussion

Objectivity and Perception

The stone stays physically the same throughout the story, but is perceived differently by each animal that interacts with it. Using this stone, we can discuss how perception is influenced by perspective and our senses, and whether there truly is one objective view of the stone. Everyday, people use their senses in order to draw conclusions and perceive the world around them, but does this mean all perceptions are necessarily correct? The story specifically alludes to René Descartes’ “Wax Argument.” Say you observe a solid piece of wax using all of your senses — smell, taste, sight, size, hardness, etc. If you melt the wax, we know that it is still the same piece of wax, just melted now. Descartes claims that there is no way to know the wax is the same using sense alone because all of the sensible properties have changed. If we also cannot rely on our senses to perceive the stone, how do we know which animal’s perception of the stone is correct? Is there just one correct perception? Are they all correct? More generally, is it possible at all to perceive objective reality with something as subjective as our senses?

As each animal experiences the stone differently, and each animal is equally reliable, students are forced to question the reliability of senses as a whole. This also leads students to question the difference between how something appears and what something actually is. Students may think there’s a way the stone objectively exists, but we only have access to how the animals describe it. This forces them to confront whether the stone can be opposing things in nature, such as rough and smooth, or if there is an objective way to know the stone. If the stone is described as rough at one point in time and smooth the next, do these perceptions alter the nature of the stone? Is perceiving the stone distinct from knowing how it truly is? This forces students to question whether the appearance of something contributes to its objective nature. Students can recognize that the stone appears differently to different animals, which may lead them to conclude that appearance does not affect the nature of something, but this is where the main tension in the book comes to light. Many students may claim that the stone’s varying appearances and its objective nature are one and the same — neither claim is wrong. This book challenges students’ views on perspective and whether something can be multiple things at once, as well as if someone’s lived experiences affect their perception. It also questions objectivity and whose view on something matters most.

Change and Constancy

Near the end of the book, we learn that the environment around the stone has changed, and it’s now submerged in water. While the stone itself hasn’t changed physically at all, it can no longer be interacted with in the same way, arguably changing its value. This prompts students to think about how change affects the way we see things and whether we view change as good or bad. Does changing how something appears change the substance of the object? Does changing the way we interact with an object change its value or detract from its former value? Does the stone remain valuable even though it can’t be seen or used in the same way as before? Many students may relate to the discomfort of change, and this conversation allows them to reflect on the role of change and its effects.

The story also encourages students to think about the passage of time as a form of change. Over time, the stone ends up in different environments, ultimately ending up in the water. This brings students’ attention to the idea of changing with time and how we might end up somewhere different than we originally started. We may not even realize that we or things have changed. How do we know that something has changed? This topic provides a gateway to discussing ideas like why change over time can be difficult, and if all change is inevitable. Discussions around change can equip students to feel more comfortable with accepting it.

These ideas of change can also be contrasted with constancy, and what that means to them. Discussions may compare things that stay the same to those that don’t, and what roles those things play in our lives. Is there value in things staying the same? Does it bring reliability? When does something shift from being reliable to being overly stagnant? With these topics, students are able to dig into the significance of change, and whether things are no longer important if their roles change. Many things do change — what does it mean to know and accept change?

Memory

At the end, the stone is revealed as a memory. This encourages students to consider the importance of memory and the role it plays in our lives. Looking back on the stone, how have the ways it’s remembered differed and whose memory do we trust? Are all the memories equally important and accurate? How does the way the stone is remembered compare to the way we remember things in our own lives? Students can think back to experiences or events from their past and bring those into the discussion.

Questions for Philosophical Discussion

Objectivity

- How is the stone described? What adjectives are used to describe the stone

- Can the stone be big and small? Dark and bright? Rough and smooth?

- Can something be two opposing things at the same time?

- Are any views of the stone wrong?

- Are any of the descriptions of the stone more true than others?

- Can two people disagree on something and both be right?

- Is there a true “nature” of the stone that describes how it actually is?

Perception and Perspective

- What affects how the animals perceive the stone?

- Which animal’s perception of the stone do you agree with the most? Why?

- If the book is always talking about the same stone, why are there so many different descriptions of it?

- Is there a difference between how the stone is perceived by others and the way it truly is?

- Can we trust the way our senses perceive the stone?

- Have you ever seen something or thought about something differently than your friends?

- How do you decide which point of view is correct? Can multiple viewpoints be correct?

Constancy and Change

- Does the stone change at all in the book? How?

- Is there anything that never changes in the world?

- Is change good or bad? Why?

- Should things change? Should things stay the same forever?

- What does it mean for something to be constant?

- For something to change, does time have to pass?

- Is it possible for something to have contrasting appearances without time passing?

Memory

- Is the stone still important even if it’s just a memory now?

- What is a memory?

- What does it mean to remember something?

- Are there things in your memory that don’t exist anymore?

- Are the things you remember still real even if they don’t exist anymore?

- Why are memories important?

- Is it okay to forget some things?

- How do you want to be remembered?

Find tips for leading a philosophical discussion on our Resources page.