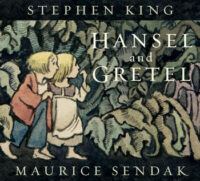

Hansel and Gretel

Book Module Navigation

Summary

This dark and imaginative retelling of the classic Brothers Grimm tale follows two children, Hansel and Gretel, who are abandoned in a dangerous forest and must find their way home. Along the way they encounter hunger, fear, and a witch who tempts them with promises of comfort but harbors cruel intentions. With Sendak’s haunting illustrations and King’s suspenseful storytelling, the book highlights themes of survival, trust, temptation, and resilience. Readers are invited to reflect on what it means to face danger, make choices in difficult circumstances, and rely on one another for strength.

Sensitivity Note: This story includes frightening imagery, abandonment by parents, and the children’s violent defeat of the witch. Educators should be mindful of the intensity of these themes for younger readers and prepare supportive discussion.

Guidelines for Discussion

Hansel and Gretel lends itself to philosophical exploration because it raises questions that children already wonder about in their daily lives: What does it mean to be brave? How do we know whom to trust? Is it ever okay to do something wrong in order to protect yourself? When used in the classroom, the story can invite students into what Matthew Lipman called a “Community of Philosophical Inquiry,” where the goal is not to arrive at a single right answer but to consider many perspectives together.

One natural starting point is the role of fear and courage. Children often assume that bravery means not being afraid, but Hansel and Gretel clearly feel terrified even as they continue to act. This opens the door to distinguishing between feeling fear and acting with courage, and it also allows children to share personal connections—moments when they themselves felt scared but went forward anyway. In this way, the story helps them recognize that courage comes in many forms.

The parents’ abandonment raises difficult questions about family and responsibility. Was it fair for the children to be left in the forest? What do parents owe their children? These questions encourage students to think about the roles and responsibilities that structure family life, and to test principles against cases: if parents cannot provide for their children, what should they do? Younger children may gravitate toward questions of fairness, while older ones may notice the pressures and hardships that might drive the parents’ decision.

The witch’s deception provides another rich entry point. At first she appears kind and generous, but she later reveals her cruel intentions. This tension between appearances and reality resonates with children’s own experiences of trust and mistrust: How can we tell if someone is trustworthy? Do good actions always mean good intentions? Here the story connects to ordinary life, such as being promised something by a friend or encountering an advertisement that turns out to be misleading.

Finally, Gretel’s act of killing the witch brings the discussion to questions of morality, harm, and survival. Was she justified in doing what she did? Is self-defense different from doing harm for other reasons? These questions can help children recognize the complexity of morality: sometimes we face choices where no option is entirely free from harm. Asking whether desperate circumstances change what is right and wrong can help students see how context shapes our moral judgments.

Facilitators should aim to keep the discussion open-ended, avoiding the temptation to close the story down to a neat moral lesson. Instead, the emphasis should be on encouraging students to give reasons for their views, to listen carefully to one another, and to compare different perspectives. Even when students disagree, facilitators can draw connections: “Some of us think courage means acting despite fear, while others think it means not being afraid—what do these ideas share in common?” In this way, the story becomes a shared space for reflection, where children learn not only to think critically about difficult questions but also to practice listening, comparing, and building on one another’s ideas.

Discussion Questions

Fear and Courage

- Hansel and Gretel were afraid but kept going. Can someone be afraid and still be brave?

- What does it mean to be brave—facing danger, or not feeling afraid?

- Have you ever felt afraid but done something anyway?

Family and Responsibility

- Was it fair for Hansel and Gretel’s parents to leave them in the forest? Why or why not?

- What do parents owe to their children?

- Do children ever have responsibilities to their parents?

Trust and Deception

- Why did the witch seem kind at first?

- How can we tell if someone is trustworthy?

- Have you ever trusted someone who wasn’t what they seemed?

Good, Evil, and Survival

- Was it right for Gretel to push the witch into the oven? Why or why not?

- Do desperate situations change what is right and wrong?

- Can people do bad things for good reasons?

Suggested Activity: Fear Maps

A powerful way to help students connect personally with the themes of Hansel and Gretel is through creating “fear maps.” Begin by giving each student a blank sheet of paper along with crayons, markers, or colored pencils. Invite them to imagine a place—real or imaginary—where they might feel scared. This could be a dark forest like the one Hansel and Gretel enter, or it could be something drawn from their own lives, such as a dark room, a storm, or even a situation at school that feels intimidating.

Once students have identified a place of fear, ask them to draw it on their paper in whatever way makes sense to them. After they have sketched the setting, encourage them to think about what could bring them courage or comfort in that place. They might add a flashlight, a trusted friend, a protective animal, or even a symbol like a star or a shield. The idea is not to make a perfect drawing but to use images, symbols, and colors to express both the feeling of fear and the sources of courage that can help them face it.

When most students have finished, give them the option to share their maps. Some may feel comfortable presenting to the whole class, while others may prefer to share in smaller groups or pairs. Encourage them to explain both what makes the place frightening and what they chose to represent courage. This sharing process allows students to see that fear is a common human experience and that courage can take many different forms.

As a facilitator, guide a reflective discussion after the sharing. You might point out patterns, such as how often friends, family members, or light sources appear on the maps, and connect these ideas back to Hansel and Gretel’s story. For example, you might note that just as the siblings found courage by relying on one another, students too often draw strength from relationships. Finally, highlight that courage does not mean being fearless, but rather finding ways to move forward even when we are scared. In this way, the activity not only deepens engagement with the story but also fosters empathy, self-reflection, and mutual understanding within the group.