The Trouble with Unpaid Internships

As any college student knows too well, cold winter weather signals the beginning of an annual rat race that permeates the university experience – brace yourselves…it’s internship application season. Over the next few months, students across the nation will be scrambling to land a job for the summer. They will plea for nepotism from friends and family, search the web for any morsel of opportunity, or cold call alumni in a last ditch email barrage of desperation; all of this in an attempt to lockdown the all-important internship offer.

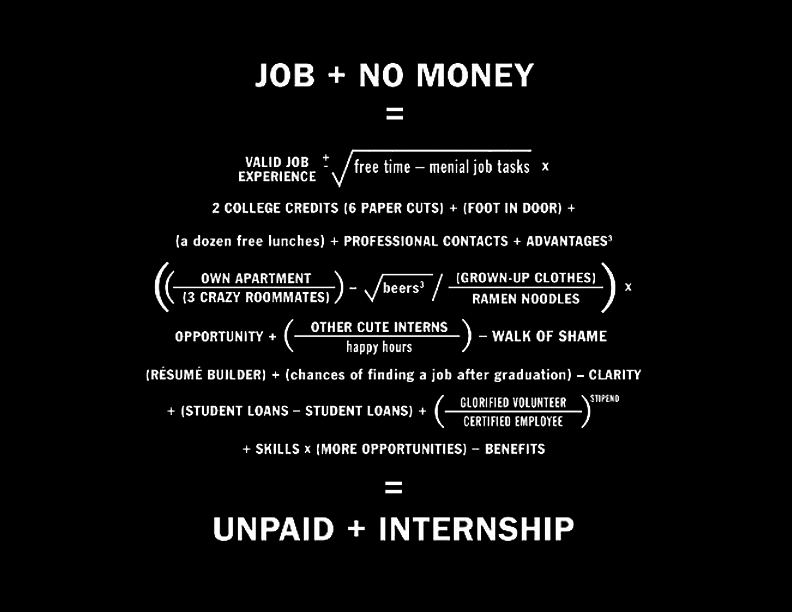

What follows from this deluge of career-minded college students bidding for summer employment is that many of these job-seekers will be scooped up by companies looking to turn a student’s ambition into free labor. The yearly number of unpaid internships is between 500,000 and one million, a great pool of untapped talent that employers are able to draw on for free.

Despite a surge of related lawsuits, this issue is often overshadowed by more politicized issues concerning the American workforce. But when we take a look at the larger ethical implications of unpaid internships it is clear that this issue is critical in understanding what it means to be part of the modern workforce.

The Department of Labor (DOL) has outlined 6 criteria that employers must follow in order to bypass the normally non-negotiable minimum wage. These standards were developed in an attempt to rectify some of the mistreatment of interns by making their voluntary internships more educational than exploitable.

The problem is that many times the requirements of these laws and the demands of a summer employer are not one in the same. Many firms and institutions go to great lengths to ensure the rights of their interns are not violated, but its easy to find horror stories of internships where employers had a very different understanding of the differences between education and labor. The DOL makes it very candid that institutions cannot gain any “immediate benefit” from the work of an unpaid intern, an expression that some employers have interpreted very loosely when assigning interns menial tasks or expecting them to hold the same responsibilities as entry-level employees.

Increasingly, internships have become the standard tool in building a resume, with many students sacrificing pay for a more prestigious opportunity. This puts lower-income students at a disadvantage in the job market. Those with dreams of working in non-profit, journalism, politics, or research are held back by their inability to take jobs that don’t pay. Many students do not have the privilege of taking an unpaid internship because they are forced to take a job that can provide them with the financial backing they need to manage the ever-increasing costs of higher education.

No matter how qualified, students who do not come from a wealthy background are often forced to sacrifice aspirations for jobs that pay. Although the job-market may be showing some signs of improvement, employers are more selective than ever when selecting from the immense pool of college graduates. Competition is intense and an employer’s obsession with internships can undermine the credentials of low-income students who couldn’t sacrifice three months of potential income for a stanza on their resume.

Are employers using eager students as mere means in an attempt to maximize their profits through free labor? Should schools be forced to provide a stipend for summer employment to even the playing field? The solution to this problem isn’t simple by any means, but unpaid internships are undermining traditional notions of what it means to work hard and achieve something for it. Interns deserve real compensation, and should be unsatisfied with vague promises of future employment or the intangibility of a supposedly educational experience.