Do Great Video Games Require Suffering?

A Soulslike is a video game that shares similarities with installments from the Dark Souls series, as well as other similar games from developer FromSoftware. Infamous for their high levels of difficulty, the Dark Souls games are loved by many and despised by many others, and are often considered something of a bar when differentiating the “hardcore” or serious gamers from their more casual counterparts. Many games in the souls-like genre are also highly rated: recent additions to the genre like Elden Ring and Hollow Knight: Silksong have received almost universal acclaim from reviewers whose criticisms almost always pertain to how difficult they are.

There have been debates in the gaming community about whether they should be easier, or at least come with an optional easy mode, so that more players could enjoy them. However, many fans and developers argue that the high degree of difficulty is essential to the experience. For example, in a recent interview, the developer of an upcoming Soulslike argued that while they would be open to adding an easy mode, “what connects Soulslike players is that they are all struggling in these games” and that such struggle “has a huge value” for them. This sentiment echoes a statement from FromSoftware’s president Hidetaka Miyazaki, who stated that in their games, “hardship is what gives meaning to the experience.”

For those who aren’t fans of such games it might sound odd that some people voluntarily put themselves through “hardship” and “struggle.” What, then, is the relationship between suffering and the value of one’s experience when it comes to playing Soulslikes or other difficult video games? And would adding the option to make these games easier really detract from their value?

We might first wonder whether there really is value in beating a really difficult video game. Certainly, players who play Soulslikes seem to think so, insofar as they enjoy the experience of overcoming significant obstacles. We might think, though, that while it might be fun to finally defeat a Dark Souls boss after hours of trying and failing, there is nothing really valuable about doing so: it is, after all, just a video game, and one’s time could have been used more effectively to create art, solve problems, or do something other than move some pixels around on a screen.

This kind of argument, though, is too dismissive. We can account for the value of defeating a difficult video game by virtue of the fact that doing so is an achievement. Philosopher Gwen Bradford argues that achievements are valuable because in achieving something we are allowed to “exercise characteristic human capacities, to fully express aspects of our nature, and to fully ‘be all we can be’.” Specifically, Bradford notes that one of the fundamental human capacities that we exercise in achieving something is the will: achieving something requires willing ourselves to overcome obstacles, and by strengthening our will, we become a better version of ourselves.

Here we have an argument for the value of beating a difficult video game: doing so is an achievement that exercises the will. But does that mean that a difficult video game has to be brutally difficult, to the point where the creators openly acknowledge that their players are suffering? Again, we have an argument from Bradford that suggests that Soulslikes do, in fact, bestow opportunities for even greater achievements. She considers the following example:

Smith and Jones are both writers. They both write novels of equal value. Smith’s experience writing the novel is fairly typical, alternating between the usual frustrations of the writing process, and periods that are enjoyable and productive. By contrast, Jones encounters tremendous obstacles while writing his novel: he loses his wife, his house, his dog, he struggles with mental health issues, and finds the writing process utterly agonizing.

According to Bradford, while Smith and Jones have done the same thing, Jones has achieved something far greater, precisely because of all the obstacles and suffering he went through. Here we also have an argument as to why Soulslikes shouldn’t be made easier, or come with an easy mode: in doing so, we remove the obstacles that allow for a more significant achievement.

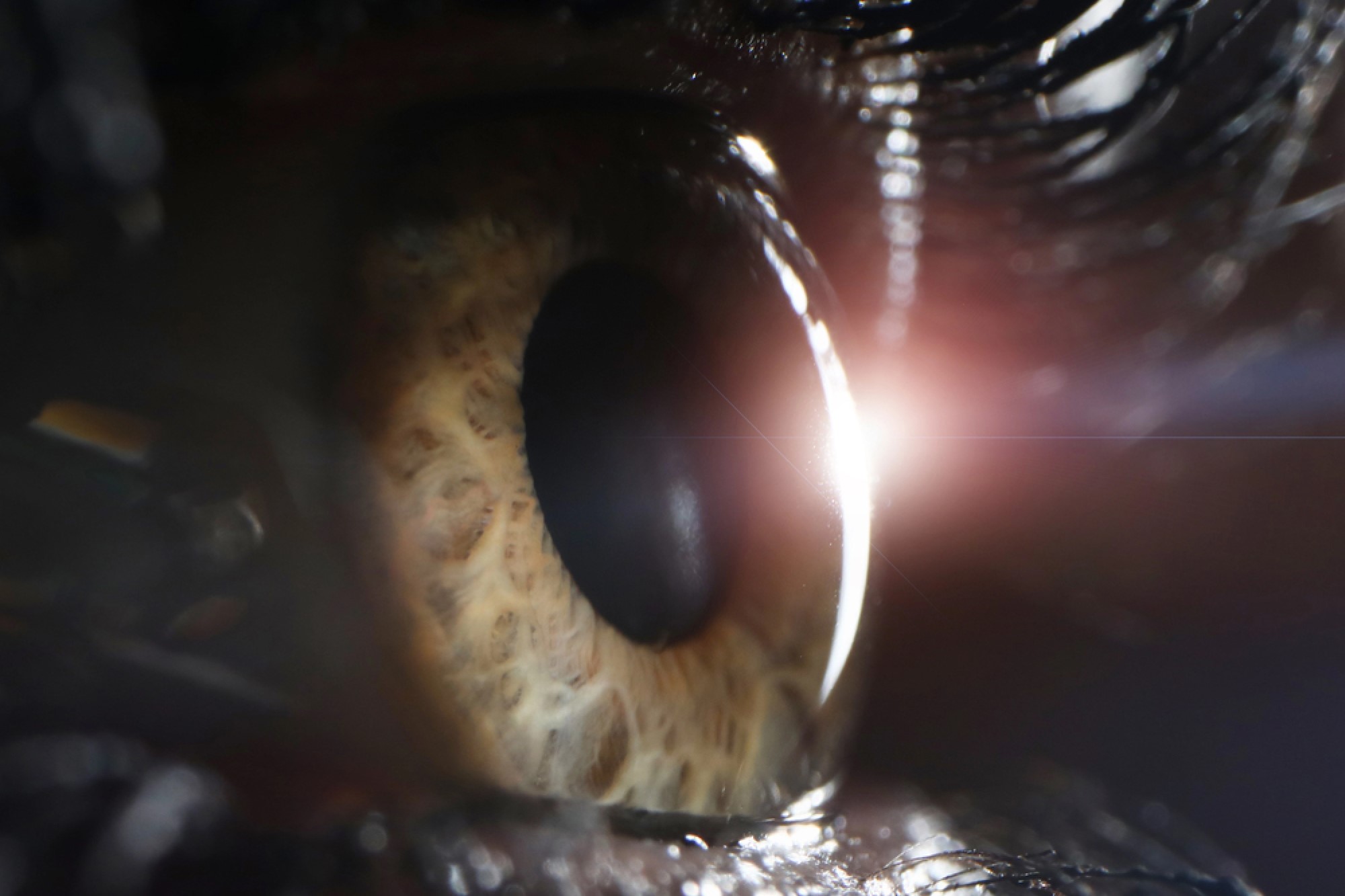

It’s not clear, though, that all obstacles one has to overcome make an achievement more valuable. Here’s an example: I am partially colorblind, and so there are some video games that are harder for me to play because I can’t tell the difference between certain colors in certain situations. In these cases, the games are harder for me, and I have to work harder to overcome obstacles created by my own misbehaving cones. While we might think that overcoming these obstacles represents a greater achievement for me, it also doesn’t seem like it would be doing me a disservice to provide a game mode that allowed me to perceive colors more easily.

Colorblindness is an example of an obstacle that may make an achievement more significant, but does not make for a more satisfying or meaningful experience playing a game. Of course, there are other obstacles I face when it comes to playing difficult video games, as well. For example, as I have gotten older, my reflexes have slowed, I have lost patience when dying over and over again, and I just don’t have enough time to get really good at difficult games. When compared to someone who is, say, younger than me and has more time on their hands, it seems like I have to overcome more obstacles than they do. Are these also obstacles that game designers should make accommodations for, perhaps in the form of a game mode for elder Millennials with full-time jobs?

Fans of Soulslikes would likely say that this is a step too far: while an obstacle like colorblindness should be accommodated, being employed shouldn’t. But it’s not clear why not. After all, when it comes to how much we are suffering when playing a Soulslike, I, as a man in his forties with a job, am suffering more than someone with spryer joints and more free time. In terms of quantity of suffering and number of obstacles to overcome, then, I would be having the same experience on an easier game mode than someone else would on standard difficulty.

So here we have the makings of an argument: if the suffering one experiences when playing a Soulslike is valuable because it creates the conditions needed for greater achievements, but different people suffer to different degrees because of their abilities and circumstances, then creating an easier mode in a difficult game will allow more players to experience equivalently significant achievements.

When we consider how game developers might accommodate more players, however, we run into a problem. After all, adjusting a game’s difficulty is not necessarily a simple matter of adjusting the value of a few variables; it might impact the intended experience and vision of the game designers. Perhaps, then, there still needs to be a baseline level of difficulty that allows a Soulslike to maintain the essence of what makes it a Soulslike, regardless of whether some people will suffer more than others when playing it.

So let’s return to our first question: we’ve seen that suffering through a difficult video game can result in a significant achievement, but is such suffering necessary? Could we, for example, still have a rewarding experience playing a game in the Dark Souls series if it wasn’t punishingly difficult?

Maybe we could. As an example, consider two copies of Alexandre Dumas’ 1846 classic The Count of Monte Cristo: one is a normal, standard paperback, and one is a hardcover version that snaps shut if you don’t read the pages quickly enough. Both contain the same plot, characters, and daring adventure, but reading one involves significantly more suffering than the other.

Presumably, we wouldn’t think that reading the booby-trapped version of The Count of Monte Cristo is a more valuable experience than reading the normal version just because it involves more suffering. This case illustrates that mere suffering does not necessarily add anything of value to a challenging experience. Indeed, this kind of argument has been used to criticize some Soulslikes for inflicting suffering for suffering’s sake: there is a point at which a game can become unnecessarily unfair or difficult such that the struggle no longer adds anything meaningful to the overall experience.

We can, then, account for the experiences of those who enjoy Soulslikes and other very difficult games by acknowledging that beating them constitutes a significant achievement, while also recognizing that suffering by itself does not make beating such games more meaningful achievements. At the same time, if part of the value of playing these games does come from a shared experience of struggle, then we might still want developers to include options to allow more players to struggle together.