No Ghosts in the Machine

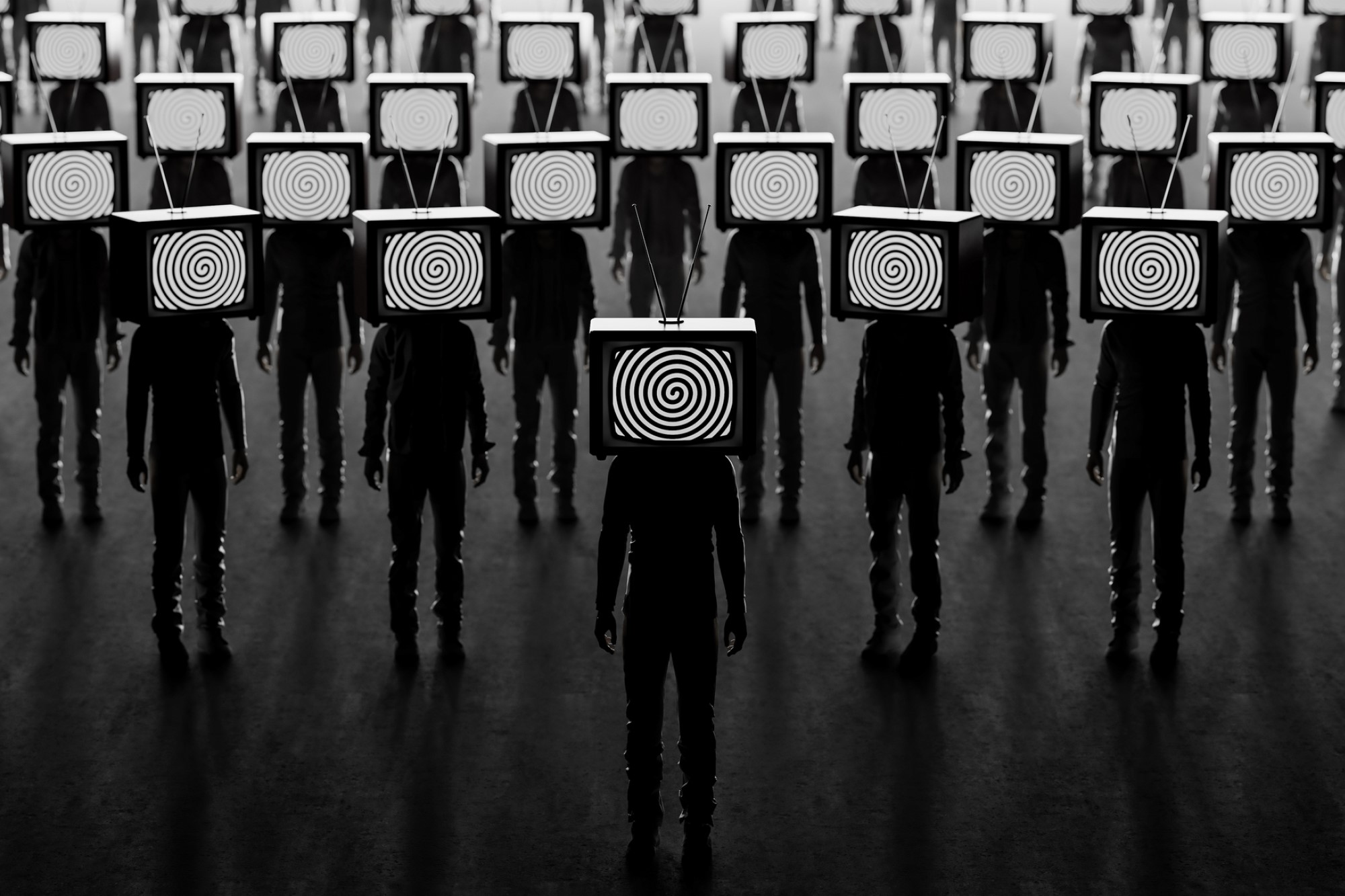

The growing power of generative AI lends credibility to what was once a fringe conspiracy theory. The dead internet theory holds that the internet is largely populated by bots. What makes it conspiratorial is that it claims that this outcome is the deliberate result of a coordinated effort by large tech companies or the government. The nature of the conspiracy theory makes it particularly difficult to refute. Any evidence one gathers from the internet could be considered compromised precisely because it comes from a supposedly dead internet. If I use facts discovered online to prove the internet isn’t dead, the conspiracy theorist can simply reply: “Of course, that is what they want you to think.”

Although it once sounded outlandish, today it is easier to see how the dead internet theory could become a reality. Deepfake photos and videos can fool people into believing they depict real humans. Recruiters now grapple with an increase in AI-generated applications. There is an increase in retractions due to questionable AI generated content, which implies that the content was not initially detected as problematic. YouTube has recently announced they will implement a new policy designed to crack down on low-effort AI content. We are witnessing AI-induced psychosis and cases of people reportedly falling in love with AI, reminiscent of the premise of Spike Jonze’s film Her.

In this sense, a central concern of the conspiracy theory has a new bite. It is entirely possible for one to have an interaction online that appears to be authentic, i.e., between oneself and another person, when that is not the case. What we face today is, in effect, a Cartesian nightmare.

Many have heard the phrase “I think, therefore I am.” This was René Descartes’ attempt at finding a belief immune to doubt. He concluded that while we can doubt everything our senses tell us, for we could be dreaming or being deceived by some evil demon, we cannot doubt the existence of our own thoughts. Doubt itself is a thought, and so long as one is thinking (and even if one is only doubting), one can know with certainty that one exists as a thinking thing.

While this is of some comfort to the skeptic, it does not resolve all of our epistemic worries. We quickly need to face questions about how we can know things about the external world, including the problem of other minds. While our everyday interactions seem to be filled with people who have minds, one cannot know what the true contents of other beings’ inner lives are like. When one uses the method of doubt, one only reveals the existence of one’s own mind. Cartesian doubt can quickly lead to solipsism, the theory that only oneself exists.

Now, in light of the technological strides in generative AI coupled with the way we have deeply integrated the internet into our social and political lives, the question of other minds takes on a new significance. When I interact with someone in real life, I don’t bother to question whether I am talking to an actual person. But online, when reading a comment or receiving an email, I increasingly wonder: Is what I am interacting with real?

I think we can break this problem down into two distinct questions:

1) Content Authenticity: When consuming content, e.g., videos, photos, articles, and music, we must seriously ask: Was this created by a human? While there are signs that something might be generated by AI, it’s reasonable to assume those signs may become more difficult to spot as technology improves.

2) Interpersonal Authenticity: When interacting with another person via the internet we must seriously ask: Am I interacting with a human?

These questions are epistemic but with a deeply metaphysical subject matter. Ultimately, I want to know how I can know something (the epistemic bit) about the nature of what I am interacting with (the metaphysical bit).

There are a lot of reasons why we might be interested in knowing the answers to these questions. One answer I can see to the question “Why should I want to know what I am interacting with?” relates to the beliefs we form about other people in the world. When we form these beliefs based on AI bots, rather than real people, our beliefs run the risk of missing the mark. We falsely believe we know what people are like.

For instance, imagine you visit an internet forum where your political adversaries gather to see what they think about an event. You open up a thread to see the hot takes. The consequence? You come away from your investigation with new beliefs. This is what they think. This is what they are up to.

But if what you have read is primarily produced by AI, then while you think you have read a sample of your political adversaries’ opinions, you have not. What you have read is an AI’s attempt at representing them.

Or imagine arguing with someone over the internet in the comments about how your country should respond to an ongoing war. The exchange might occur over several days of call-and-response posting. You find yourself staying up at night replaying your argument in an angry state of disbelief that someone out there could have such an abhorrent political view.

But, as the dead internet theory supposes, what if this person was not really a person and simply an AI programmed to argue the opposite position of anyone it interacts with? Not only would you have a false belief about a person in the world, but you would also have spent time being mad at something that was doing precisely what it was designed to do. It’s like getting mad at a toaster for toasting bread.

While misrepresenting another group’s ideology is problematic, the perils of a dead internet run deeper than this. It is difficult to imagine what a dead internet really implies and that is because for most of us it feels reasonable to assume that, at least in its early days, the content we consumed was real in some meaningful sense. Even if there are more bots now, surely this doesn’t mean that every aspect of humanity is gone.

But as linkrot proliferates, bot activity increases, and AI capacity improves, the possibility that one’s online experience drifts further away from reality increases. Even if there are other real people out there, the space between everyone may become too far for any individual to traverse. What horrifies me most about dead internet theory is not the conspiratorial possibility, that someone is out there pulling the strings. It’s the opposite. It’s the possibility that there is no one at the helm and that we are deeply alone. The idea that everything I read, watch, and listen to is generated by a machine is alienating. It is inhuman.

Generative AI has already brought to the foreground many serious issues. Much has been said about the trustworthiness of AI, the biased data it involves, the ridiculous amount of energy consumption it takes, the loss of important skills it will usher in, and the worker displacement it might create. We now have to add to this pile the Cartesian problem of other minds.

So, what should we do with the knowledge that there is no ghost in the machine that we built?