Fighting Fire with Water

Last month, I wrote a piece on the difficulty of separating violence and political ideology. To briefly recap: what makes this separation so difficult is the nature of the state. States are historically and conceptually tied to the sanctioned use of violence to enforce laws, so it is ultimately difficult to separate the two regardless of your political views.

However, there have also been significant advocates for non-violence in the political sphere. Martin Luther King Jr. and Mahatma Gandhi both advocated for non-violent civil disobedience. Simone Weil urged us to strive toward being a society capable of non-violence. And, of course, many non-violent political movements throughout history have fought for justice and peace.

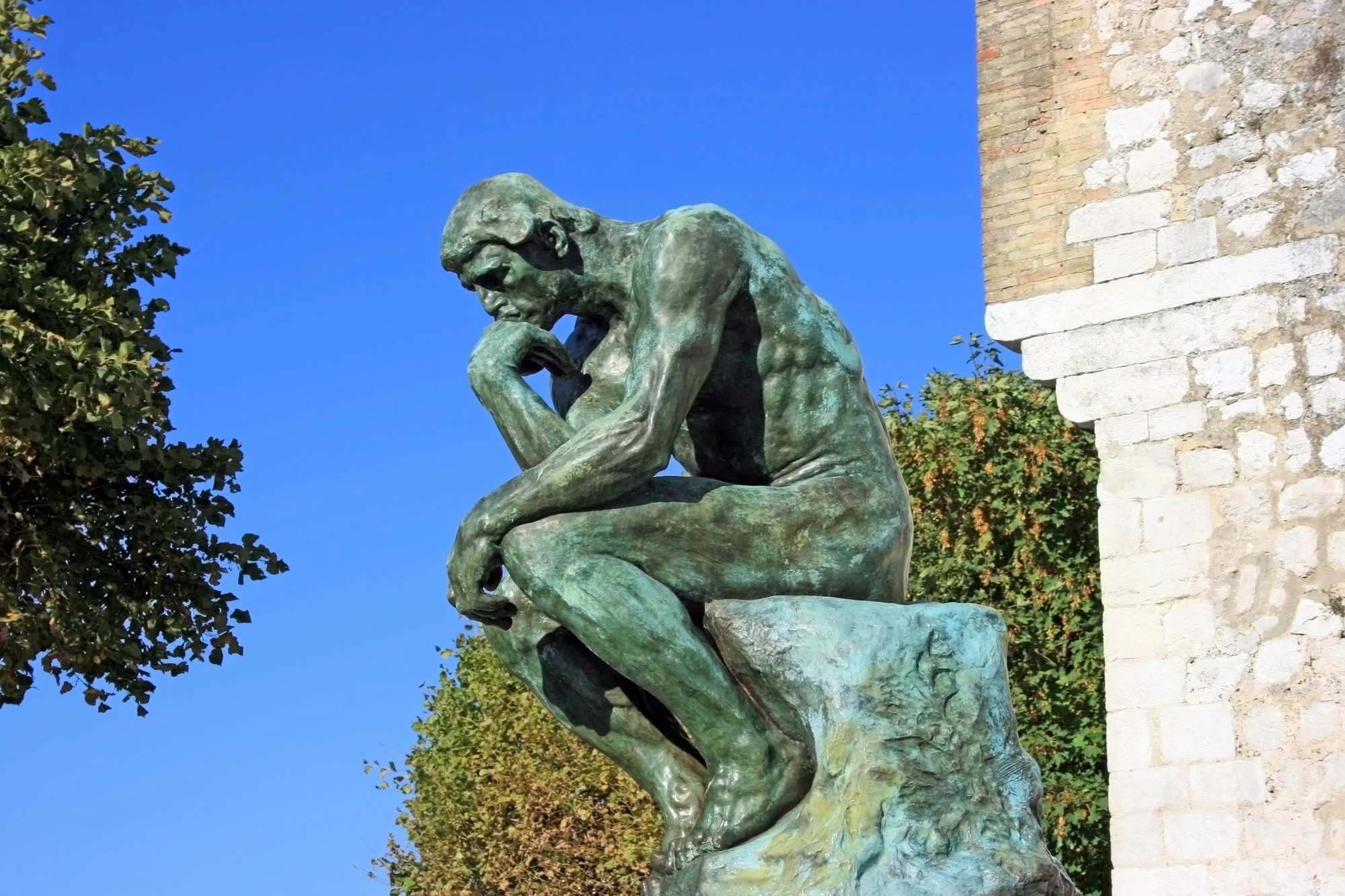

In this article, I want to explore what a non-violent political ideology might look like in theory and in practice. To do this, let us turn to the wisdom of the Buddha.

Nestled within the Majjhima Nikaya is a sutta that illustrates the core of non-violent ideology titled The Simile of the Saw. The most relevant portion goes like this:

Monks, even if bandits were to carve you up savagely, limb by limb, with a two-handled saw, he among you who let his heart get angered even at that would not be doing my bidding. Even then you should train yourselves: ‘Our minds will be unaffected and we will say no evil words. We will remain sympathetic, with a mind of good will, and with no inner hate. We will keep pervading these people with an awareness imbued with good will and, beginning with them, we will keep pervading the all-encompassing world with an awareness imbued with good will — abundant, expansive, immeasurable, free from hostility, free from ill will.’ That’s how you should train yourselves.

Here, the Buddha is teaching his followers just how deep a commitment to non-violence goes. There are a few crucial points to note to help us understand what is going on.

It is notable that the Buddha focuses on the attitude the victim must take toward the wrongdoer. He tells his followers not to get angry and to continue feeling goodwill toward their aggressor. But this is deeply counterintuitive. If anger is not justified toward people sawing you up, when could it possibly be justified? What could make this make sense?

First, the Buddha is trying to teach his followers how to alleviate their own suffering. One key insight early Buddhist thinkers had about human psychology is that suffering is ultimately a frame of mind, a way of experiencing the world. Consider the novice runner and the experienced marathoner. To a novice, running feels painful and maybe even synonymous with suffering. But to the expert, the pain of running ceases to be a problem; for some, it may even become part of the joy of running. Whether running causes suffering depends on your state of mind.

Buddhists have long understood that some human ailments are unavoidable. Old age, sickness, and death come for us all, and there is little we can do about our bodies failing us. The Buddha frequently talked about the pain that accompanies getting the things we want and then losing them or the pain that comes with failing to get what we want in the first place.

However, we do seem to have some modicum of control over our minds. So, the Buddha promises a path of freedom from suffering, and this path requires us to practice seeing the world in a new way. The troubles we face become problems only if we let them bother us.

Of course, this is easier said than done, which is why Buddhist practice contains a large tool kit of meditation practices designed to help one overcome the suffering that accompanies human life.

Second, The Simile of the Saw makes more sense when we think carefully about anger and wrongdoing. Whether we realize it or not, when we become angry we hold certain assumptions about reality. Initially, we might think that these bandits sawing us limb from limb really ought not be doing that, and that because they are doing it, they deserve to suffer.

But the Buddhist view asks us to reconsider these assumptions. Why do people act wrongly in the first place? Why are these bandits sawing me limb from limb? The answer matters. If I learn, for instance, that the bandits are acting under extreme mind control, then my anger is misplaced. If the cause of their wrongdoing can be traced to someone else, then my anger should be directed towards them instead.

The underlying assumption here is that anger only makes sense when the subject of our anger has reasonable control over their actions. And here the Buddhist worldview steps in to correct our understanding of wrongdoing. According to Buddhist thinkers, wrong action is not free action. We act wrongly because of reactive attitudes that unfold according to the karmic laws of nature. It is worth noting that the word karma is etymologically linked to the word action, so the laws of karma are really the laws of action. Effectively, there are laws of action, behavior, and emotion that are simply not up to us.

If this is true, if wrong action is unfree action, the message of The Simile of the Saw is suddenly sensible. If bandits are sawing you limb from limb and wrong action is unfree, then getting angry at them is like getting angry at fire for burning. Anger fails to appreciate the way the world actually is. And if we pair this with the primary goal of Buddhism – ending suffering – then getting angry only increases your own suffering. If you want to end suffering, don’t get angry. If you want to respond to the world as it actually is, don’t get angry.

Of course, accepting this lesson depends on accepting quite a lot from the Buddhist worldview. There is not much room for robust free will, for example, a view many of us desperately cling to. It is also important to recognize that there are better and worse ways at processing anger. The Buddha does not advocate for the harmful repression of negative affective states and I do not mean to suggest as much here.

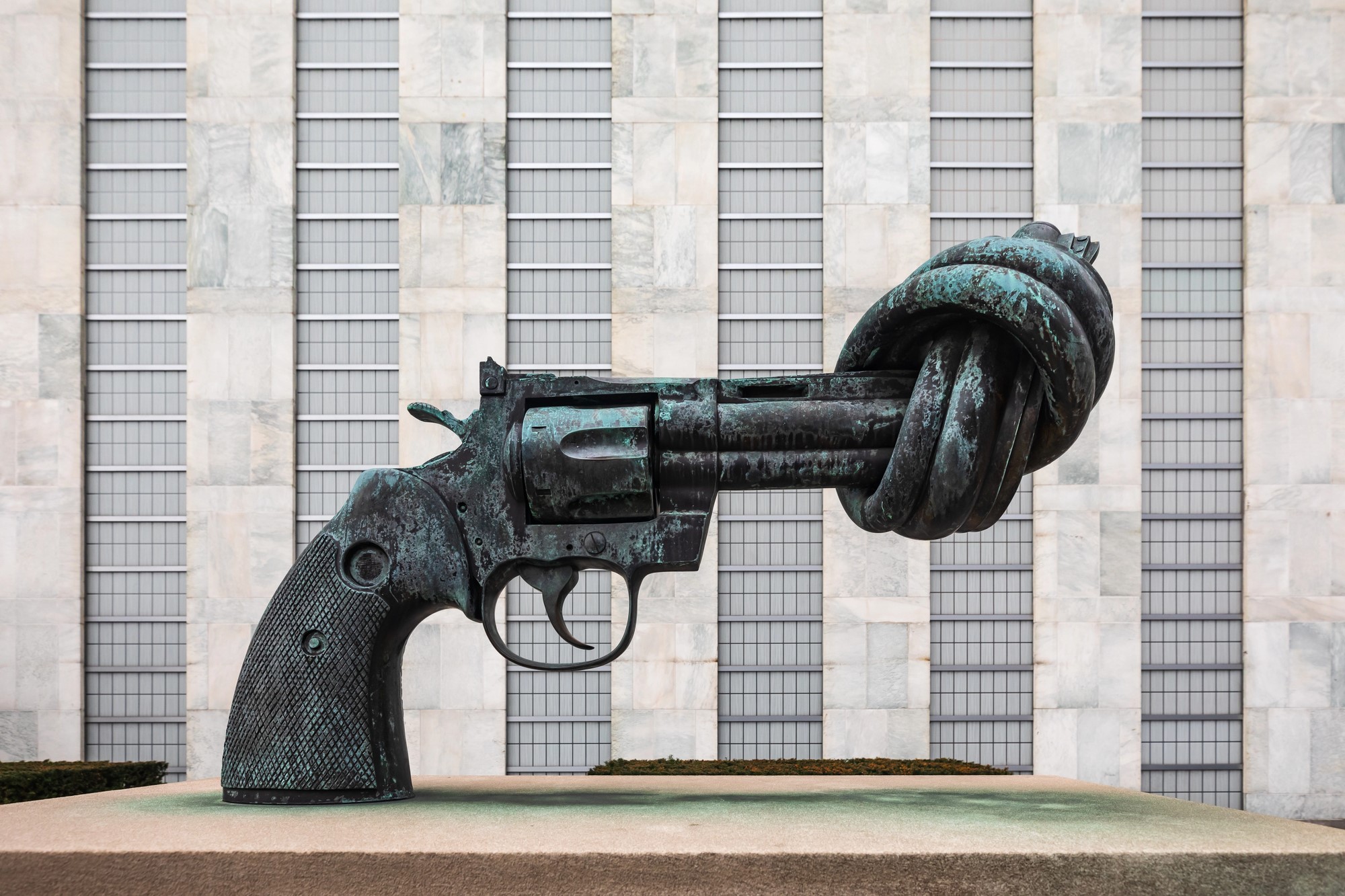

However, if you are on board with this point of view (or just want to see where this goes), what can the Buddhist picture of the world tell us about what a non-violent political ideology looks like? Consider legal punishment. Punishment is one place where the violence of the state is especially hard to ignore. What does a non-violent ideology rooted in Buddhist thought tell us to do with these bandits?

First, the bandits do not deserve to be harmed. Since most forms of punishment require harming the wrongdoer, they also do not deserve punishment. Conversely, they deserve help. From a Buddhist perspective, they deserve compassion and sympathy. What they really need is help transforming themselves into beings who neither suffer nor cause others to suffer.

Second, the bandits do not deserve to be locked in prison indefinitely. Throughout Buddhist philosophy, there are several instances where prominent monks give advice to rulers and kings. In Nāgārjuna’s Precious Garland (which you can read for free here), he explains how to deal with criminals. His advice is consistent with The Simile of the Saw. For minor crimes, do not imprison people for long, just a few days at most. Make sure that the prisoners are fed, clothed, and washed. For the most violent wrongdoers, do not even bother with imprisonment, simply banish them. Send them away from others so they cannot harm anyone. Nāgārjuna is careful to specify that the banishment should occur without killing or tormenting the wrongdoers.

A true, deep commitment to non-violence can be difficult to process given the history from which most modern societies emerge. In the United States, where the prison population is one of the largest in the world at nearly 2 million people, the idea that long-term sentencing should be abandoned seems like fantasy. But if one is committed to non-violence, then surely it makes sense to disband violent political institutions like the prison.

While there are provisions for imprisonment within Buddhist ideology, it is unlikely that the Buddha would find much merit in the modern prison industrial complex we have today. It is plausible that the most fitting advice we could draw from a non-violent political ideology rooted in Buddhist ethics would be to advocate for the abolition of prisons.