How Can We Know If a Bill Is Beautiful?

The “Big Beautiful Bill” just passed in the Senate and is likely to become law. Depending on who you ask, this bill is either a historic win, a major compromise, or a total disaster.

But with so many competing takes, how can we know what to believe?

One option is to look at the online breakdowns, news articles, or the whitehouse myth vs. fact page, all which try to explain the bill. However, if you are still skeptical, perhaps because these summaries feel overly simplified, vague, or partisan, you might be interested in reading the bill for yourself.

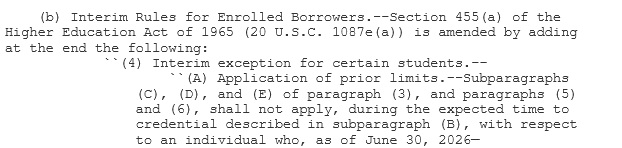

Fortunately, you can. All you need to do is check out the text of the Big Beautiful Bill conveniently placed online here. But, if you are like me, you will quickly be humbled by text like this:

Bills often amend existing laws by using in-line edits. Instead of rewriting the law, bills specify which sections of a previous law to modify and what text to add, modify, or remove. There are some good reasons to write a bill this way. It is precise, it allows lawmakers the ability to target parts of the law without rewriting the whole thing, and it helps preserve legal continuity. This approach makes sense if you are a lawmaker. For the public, it makes bills unintelligible.

In order to truly understand this bill, you would need to pull up and read every bill that this bill amends. Then, you would need to open the Big Beautiful Bill and systematically check the in-line edits across hundreds or thousands of pages of dense legal text. The Big Beautiful Bill alone is over a thousand pages, and the bills that it amends all contain sections, subsections, and subparagraphs, making it a sprawling mess. Even the lawmakers who have created the bill cannot possibly understand it in its entirety.

This problem is not trivial. John Rawls argued that a just society is one where the social and political institutions are known to, or at least reasonably believed to, align with a shared sense of justice. But how can a people judge whether a massive bill aligns with justice if they cannot read it?

There are a few ways we could increase the readability of law.

First, bills could include hyperlinks that link to the laws they amend. Second, lawmakers could produce a version of the updated laws that exclude the in-line edit language before the bill is passed. Third, we could impose limits to the size and scope of bills.

Adding hyperlinks would allow people to more easily move between a proposed bill and the laws it amends. While it is certainly possible to copy and paste the names and sections of laws being modified, adding hyperlinks removes the barrier of inconvenience. It also ensures that when I want to check what is being modified, I am looking at the correct version of the law being updated.

By publishing a version of the law that shows the proposed edits in context and without language like “is amended by adding at the end the following,” one can more easily understand the changes being made. While this does not change the complicated nature of the laws themselves, removing the contextualizing language reduces the mental effort required to make meaning out of the proposed changes.

It is worth noting that if we ask lawmakers to give us a draft of what the new version of a law would look like before it is passed, this will effectively nullify some of the benefits that one gets from using in-line edits. It would double the amount of work required to produce a bill. However, the point of this thought exercise is to try and imagine what would make the law more readable and increase justice; we can work through the practical points after we have a reasonable list of demands.

If we imposed limits on the size and scope of any single bill we would also increase our ability to understand the law. Consider, the Big Beautiful Bill includes amendments about the IRS, social security, higher education, agriculture, defense and homeland security, student loans, natural resource management, health, and the government itself. If you asked me to read a 1000-page book that covered these topics, I likely wouldn’t. However, if you asked me to read a 150-page book that only covered social security, I could manage it. This is a commonsense argument: smaller texts with a focused scope are easier to understand.

Limiting the size of a bill could have some additional benefits, like reducing the number of hidden amendments and bargaining chips buried within the text. When a bill is 1000 pages long and covers everything from AI regulation to social security tax reform, it is incredibly easy to slip in controversial legal changes that may go overlooked or to use less controversial but important amendments as bargaining chips for the more controversial ones.

One could of course argue that enforcing a size and scope limit on bills would slow down an already painfully slow government. To this, I have two responses.

First, it might do that and this is not an insignificant concern. Creating a just society is demanding, and having a government that can get laws passed in a reasonable amount of time is absolutely desirable. It may be a cost that we need to weigh against the benefits of increasing the public’s ability to understand and assess the laws that govern them.

Second, while it might slow things down, it may also speed things up. One of the issues with passing large bills is precisely the fact that bills contain so much. For example, if two senators agree on changes A, B, and C, but disagree about D and E, bundling these together unnecessarily blocks progress on A, B, and C. Smaller bills could encourage a quicker resolution on the things that are already agreed upon.

Making bills smaller would also force our representatives to show their true colors. Because bills often contain so much content, it is easy for lawmakers to hide behind policies that they know are more favorable. If there is a policy about military spending and a lawmaker wants to vote to increase that spending but fears they might be accused of being a warmonger, they can simply say the reason they voted for the bill was to help ensure a school tax credit would be instituted, which they know to be more popular.

There will be limits to making the law intelligible. Making the law precise requires using technical legal terminology, not to mention the technical language of every sphere the law covers. However, this does not mean we cannot implement ways to increase the legibility of the law. If we care about justice, we should care about making laws easier to read. If we cannot read the law, we cannot understand it, and if we cannot understand it, we cannot judge whether it is beautiful or ugly, just or unjust.