The Politics of Depression

In contrast to the exuberant energy of the 2016 presidential election (for better or for worse), the 2020 election has been characterized by fatigue, anxiety, and even depression. Regardless of which candidate triumphs in the presidential election, many voters on both sides can’t help feeling daunted by the government’s inability to meet the needs of its citizens.

The language of illness has always been a useful lexicon for politics; the metaphor of the “body politic” informed statecraft in Europe for centuries, and enemies of the state have always been described as a disease eating away at that body. But for those members of the body politic struggling with mental illness, the question is how to remain politically active while battling depression, especially when the stakes are so high.

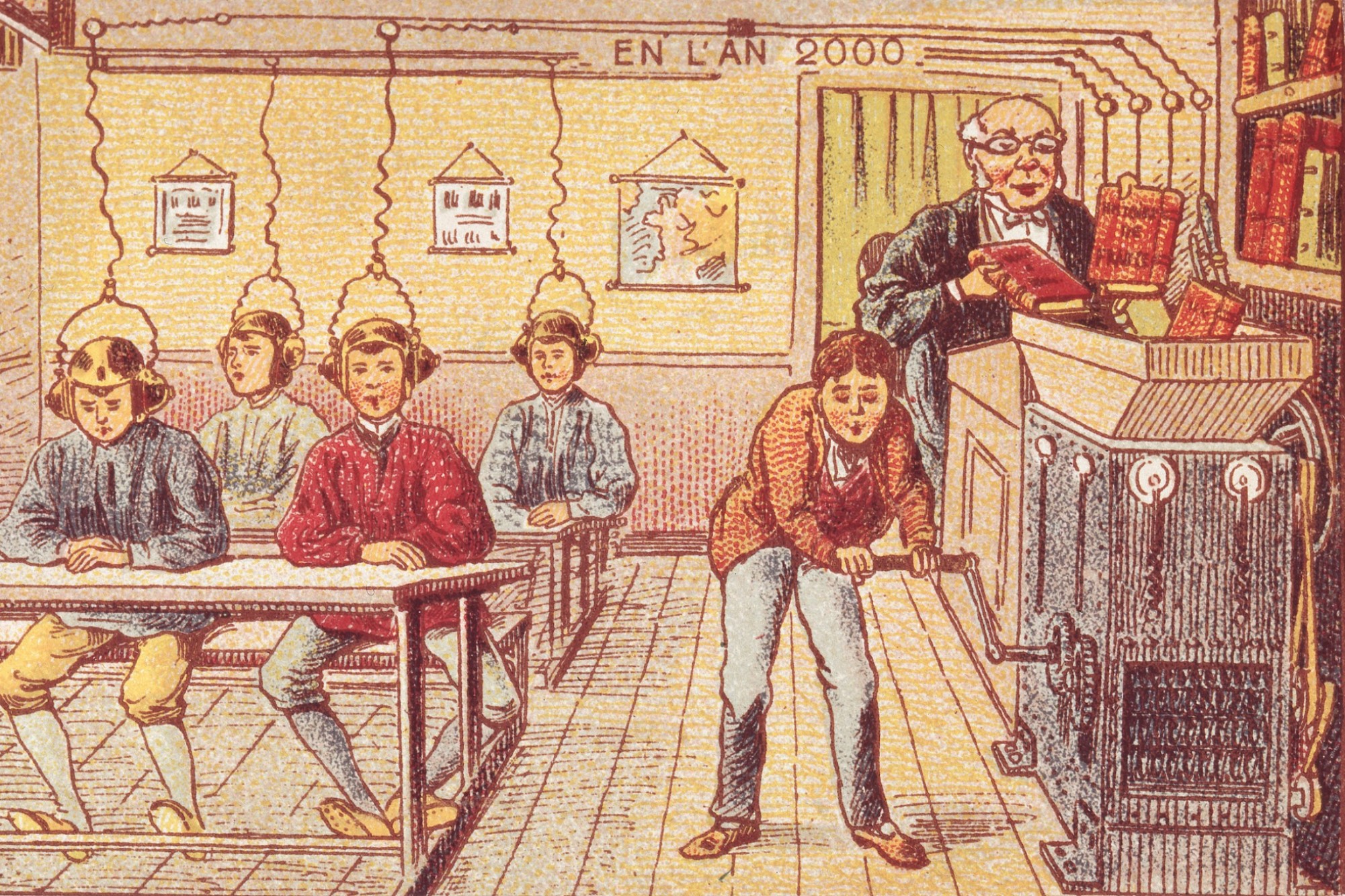

Depression may be the mental illness par excellence for political discourse under capitalism. While capitalism has been linked to schizophrenia (we are expected to be sober workers by day and hedonists by night, as sociologist Daniel Bell points out, which ultimately creates a fractured psyche), Mark Fisher draws comparisons between his experiences with depression and the mindset induced by capitalism. In his 2009 book Capitalist Realism, he writes that “while sadness apprehends itself as a contingent and temporary state of affairs, depression presents itself as necessary and interminable: the glacial surfaces of the depressive’s world extend to every conceivable horizon.” He sees a parallel between the “the seeming ‘realism’ of the depressive, with its radically lowered expectations, and capitalist realism.” As Fisher understands, enacting political change and fighting depression are struggles against a similar opponent.

Depression itself is becoming increasingly political, both in terms of how we conceptualize it and how we attempt to cure it. Danish literary critic Mikkel Krause Frantzen proclaims in an incendiary essay for the LA Review of Books that “any cure to the problem of depression must take a collective, political form; instead of individualizing the problem of mental illness, it is imperative to start problematizing the individualization of mental illness.” He asserts that “Dealing with depression—and other forms of psychopathology—is not only part of, but a condition of possibility for an emancipatory project today. Before we can throw bricks through windows, we need to be able to get out of bed.” This political approach to illness is rooted in a wider politicization of illness. For example, Anne Boyer writes in her recently published memoir about cancer, The Undying, that “Disease is never neutral. Treatment never not ideological. Mortality never without its politics.” Boyer rejects apolitical cancer treatment, noting that “Our genes are tested, our drinking water is not. Our body is scanned, but not our air . . . The news of cancer comes to us on the same sort of screens as the news about elections.” Like cancer, depression is often viewed as purely somatic, not as a condition with a basis in the material reality of the afflicted.

When we acknowledge that material reality, we create the potential to radicalize those with mental illness. However, the fatalistic mindset of depression often discourages political engagement. One study conducted by researchers at Pennsylvania State University, which argues that “that depression is a political phenomenon insofar as it has political sources and consequences,” found that mental illness “consistently and negatively affects voting and political participation.” Furthermore, “depression also has developmental consequences for political behavior. Adolescent depression has the potential to set individuals on a trajectory of political disengagement in adulthood.” The study paints this as a vicious cycle; without adequate mental health care, we become depressed, and then depression inhibits political engagement, which prevents healthcare policies from ever changing. The study concludes that though research into the neurological aspect of depression is extremely important, it is also,

“worthwhile to theorize about depression in terms of the social model, especially because the experience of a mood disorder such as depression is largely rooted in social circumstances. Depression is socially-situated in so far as it is not something that simply ‘happens’ to someone but arises out of the circumstances of life. This is compounded by the fact that traditionally disadvantaged groups disproportionately experience depression.”

So how can the mentally ill break out of that vicious cycle? There is no easy solution to this dilemma. Even recognizing that major changes that need to be enacted in order to create a liveable world isn’t always enough. As Frantzen says, “there is no reason to believe that abolishing private property ownership, or realizing a global and absolute cancellation of private debt, will relieve the suffering of depressed people with a single stroke, as if by magic.” For voters experiencing a sense of hopelessness at the polls, and who fear plunging to an even greater depth of hopelessness on election night, a radical kind of self-care is needed. Many have already pointed out the often vacant politics of “self-care,” which does not always promote social change as much as we’d like it to. But when self-care is able to foster “not competition among the sick, but alliances of care that will make people feel less alone and less morally responsible for their illness,” in Frantzen’s words, it is certainly a step in the right direction.