Rural Health Disparities and Telemedicine

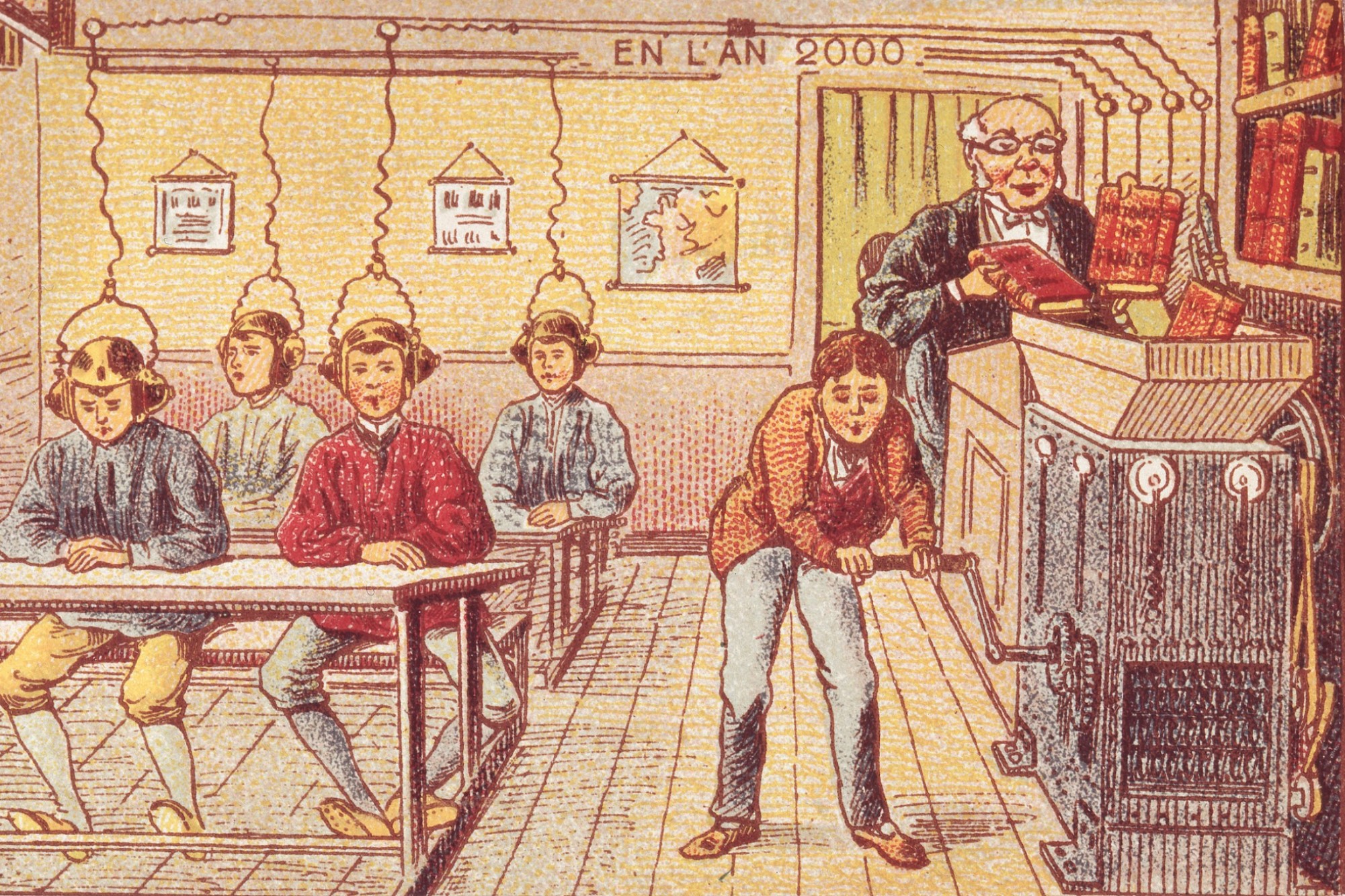

Rural America has been struggling from a lack of hospitals and physicians at an alarming rate. In the past decade, ER patients in rural communities have increased by 60% and hospitals in those locations have decreased by 15%. A potential solution to the lack of health care providers is to consider telemedicine as an option for these rural locations. Telemedicine is a remote care center which provides hospitals, clinics, or even individuals with direct access to a physician. One such company that provides this service is Avera eCARE. At Avera eCARE, doctors work out of high-tech cubicles, dressed in scrubs to look the part, but never actually physically touching or seeing their patients. Instead, they use a high-resolution camera and microphone to work with their patients and nurses or healthcare professionals at remote locations.

Dr. Brian Skow is an example of a physician who works from one of the Avera eCARE centers that provides remote emergency care for 179 hospitals across the nation. Skow was called in when a comatose, unresponsive patient came into the emergency room in rural Montana with only nurses on staff. Skow remotely instructed the nurse how to incubate the patient – inserting a tube into the patient’s throat in order to get her onto a ventilator. Without his help, this patient would have most likely died from lack of oxygen.

“If anything defines the growing health gap between rural and urban America,” The Washington Post claims, “it’s the rise of emergency telemedicine in the poorest, sickest, and most remote parts of the country, where the choice is increasingly to have a doctor on screen or no doctor at all.” And Dr. Skow’s situation is a perfect example. He watched as 5 people performed the procedure, all with careful instruction and encouragement from his remote location. To compare this to his hospital at Sioux Falls, he has to compete with an emergency physician, trauma surgeon, cardiologist, anesthesiologist, a team of 20 residents, ER nurses, and paramedics to be at the bedside. This has meant that each month telemedicine can help cardiac episodes, traumatic injuries, overdoses, and burns at a rate that is much higher than before.

There are a number of benefits generated by the move to such a system. Telemedicine helps hospitals retain doctors and recruit them because it allows for time off- and on-site support. Many critical-access hospitals are struggling to find even a single doctor or can’t keep physicians long. This technology offers the option for the nurses and physician assistants to call in for immediate health care suggestions. Another benefit is that hospitals are able to treat more patients with more intense conditions than before, as the technology allows hospitals to treat patients without needing to immediately transfer them. These transfers increase the time in which the patient suffers, and for most of these cases, every second counts. Apart from pain and outcome, transferring also greatly increase billing charges for patients. Even hospitals benefit by treating more cases and thus generating more profit.

Despite these advantages, there are still many limitations. Telemedicine costs approximately $70,000 monthly and $170,000 to install. Hospitals have to face a difficult decision in choosing between installing this technology or investing money on other life-saving machines like MRI and CAT scans.

Critics also worry that telemedicine takes the humanity out of patient-physician relationship. Instead of physically being with the patient, that crucial interaction is separated by a screen and thousands of miles. This reality can affect treatment in ways that are unexpected. Especially in remote communities, it is very common for the nursing staff to know the patient personally, but for the virtual doctor, the patient can become “less human.” Doctor Kelly Rhone, describes this phenomenon as she watched nurses from North Dakota perform CPR on a patient for over 10 minutes. One of the worst things that the remote doctor can do, Rhone argues, is withdraw care too quickly. Even when a patient has passed, it’s important for the medical staff in the room to acknowledge the situation in their own time. This obligation may even extend to being present with grieving family members.

It is important to consider then, if remote care is an adequate substitute and can offer sufficient support for the human element to medicine. Perception can play a major role in diagnosis, and if doctors aren’t seeing their patients in the same way, they will treat them differently. It may be more likely for doctors to withdraw care or save resources, compared to situations where they are with them in person.

There are also some challenges when it comes to telemedicine being used directly in people’s homes. There are apps which can help patients connect with a doctor via Facetime, text messages, and phone calls. There are some benefits to this option. For busy parents and working folk, this is a quick and easy solution to getting better fast. Some people live an hour or more from the nearest health clinic, and so to be able to describe their symptoms over the phone and get their medicine prescribed within minutes is a great benefit. However, there is also the increased risk of misdiagnosis. It can be easy to miss symptoms of larger health problems – when chest discomfort isn’t just a strained muscle, but an early sign of a heart attack, for example. In this way, reliance on telemedicine can increase risk to patients.

There is a clear injustice in our health care services in the United States for rural areas and urban locations. Telemedicine is one option for those who are suffering from lack of adequate healthcare. It increases virtual staff and gives current staff direct access to help for their situations. With the rising trend toward virtual telemedicine, we must consider what cost to patient health we are willing to accept for increased efficiency.