Vaccination Abstention and the Principle of Autonomy

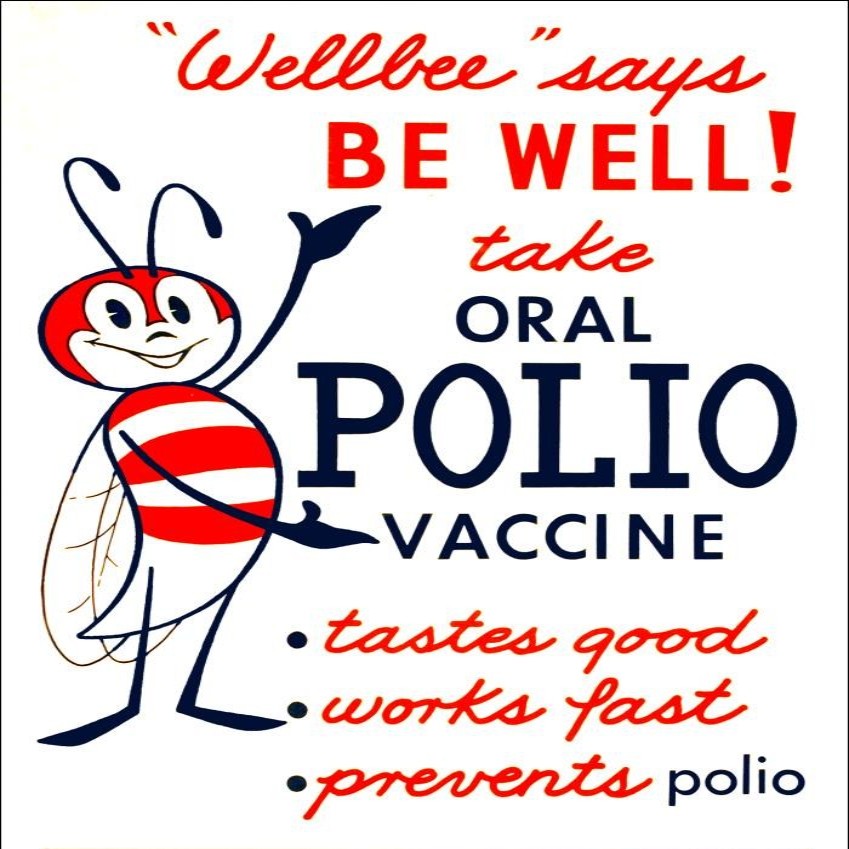

The suppression or eradication of many serious diseases in vaccinated populations has been one of the great public health successes of the twentieth century. There have always been those who resist or refuse vaccination for a variety of religious, political, or health reasons. Though there can be some risk of negative reactions to vaccines in certain individuals, vaccination is very safe for the general population.

In recent years, despite the major success of vaccination in protecting the community against diseases which may be lethal to some vulnerable persons (the very young or the elderly) such as measles or pertussis, or which may cause serious complications such as rubella and polio, the opposition to vaccination has morphed into a populist, evangelical movement whose arguments are influencing more and more parents to refuse vaccination for their children. This has reached such a wide section of the community that it now threatens to undermine, and undo, many of the gains for public health achieved by high, near unanimous, levels of community vaccination.

This movement is the reverberation of a number of vaccination related scare campaigns. In the 1970’s the DTP vaccine was erroneously linked to neurological damage. More recently, in the 1990’s the MMR vaccine was erroneously linked to autism. Though these claims have been debunked by extensive research, they continue to be the mainstay of anti-vaccination propaganda, and people often still believe that the risks of vaccination outweigh the benefits. This is currently the biggest objection to vaccination in Australia, the UK, and United States, where parents cite medical risks, including autism, as reasons for abstaining.

Vaccines are not one hundred percent effective. However, they are effective enough that if a large majority of people are vaccinated there will not be enough viable hosts for the disease to spread through the population, a phenomenon known as ‘herd immunity‘. But if vaccination levels fall below those needed to achieve and maintain herd immunity, people who cannot be vaccinated, or for whom the vaccine is not sufficiently protective enough, are put at risk.

As a response to what threatens to be, if the trend continues, a public health crisis, many governments have introduced legislation to try to force parents into vaccinating their children. One common method is the exclusion of unvaccinated children from certain activities like day care centers, kindergartens, and schools or the offering of tax credits. Such moves have naturally sparked a debate about how best to balance the importance of vaccination for public health with parents’ right to make their own choices for their children, and the general right to refuse medical treatment.

Concerns that parents are putting their own children at risk by not having them vaccinated is amplified by the fact that they are also putting others at risk – especially those people who for other medical reasons cannot be vaccinated, but also the population at large by allowing diseases to re-establish themselves in the community. It may therefore be argued that parents have a moral duty to provide the best protection to their children as well as a moral duty to contribute to the protection afforded to the whole community that results from each person doing their part by being vaccinated. But even if such a duty exists, can it outweigh a parent’s right to refuse vaccination?

Biomedical ethics, the branch of ethics which deals specifically with issues that arise in the medical sphere, (including the responsibilities of health care professionals with respect to the needs and wishes of their patients,) is dominated by a principle-based approach. The principles generally taken as fundamental in biomedical ethics are: beneficence, non-maleficence, autonomy and justice. Sometimes these principles can clash, and in such cases, there will need to be some determination made as to which principle(s) take precedence. In terms of the challenge presented by parents wishing to abstain from vaccinating their children, there is a clash between the principles of autonomy and justice. The issue is not merely a matter of individual well-being but also a matter of protecting the whole community.

Respect for autonomy is respect for a person’s right to, and capacity to, make decisions about health care and medical treatment for themselves and for those under their guardianship. In general, people place extremely high value upon their autonomy. Its priority is derived from the possibility of self-determination which is commonly considered an essential tenet of liberty and a vital condition for human flourishing. To attenuate or override autonomy in a biomedical setting is a very grave matter. This is why, as important as immunization is, the idea of forcing people to have their children vaccinated is morally onerous.

Yet, there may be a sense in which one’s autonomy may be questioned given the infiltration of the anti-vaccination movement into the mainstream. While the principle of autonomy demands that the patients be given an opportunity to make an informed choice about his or her care, the arguments of the anti-vaccination movement are based on misinformation and conspiracy theories. The possibility that many expressed preferences are ill-informed leads us to question the very possibility of “informed” choice. Can someone who is operating under the falsehoods propagated by the anti vaccination movement be said to be making an autonomous decision?

This would seem to simply be an issue of education. In an ideal world, if everyone really understood the risks of not vaccinating versus those of vaccinating, then all would choose to vaccinate. In order to respect individual autonomy, a massive effort to finally discredit the anti-vaccination movement would be preferable to trying to force people into vaccination using punitive measures, which may have the opposite effect, and galvanize their resolve.

However, educational efforts do not seem to be working, either because they are not vigorous enough, or are not penetrating the prejudice which the anti-vaccination movement’s propaganda has sown into the community. The point about propaganda is important, because it highlights the fact that people are not simply ill-informed but are actively misinformed, and that the conspiracy theory nature of the anti-vaccination movement coaches people to reject medical evidence that contradicts its position.

From this perspective, though the principles of autonomy and justice are in conflict on the level of individual and community healthcare, something else – connected with how and why people are swayed by the tactics of the anti-vaccination movement is at stake, and as a community we are faced with the more difficult question of how to bring that aspect of the issue to bear upon the adjudication of clashing ethical principles.