Just How Useful is the Trolley Problem?

Philosophy can be perceived as a rather dry, boring subject. Perhaps for that very reason, divulgers have attempted to use stimulating and provocative thought experiments and hypothetical scenarios, in order to arouse students and get them to think about deep problems.

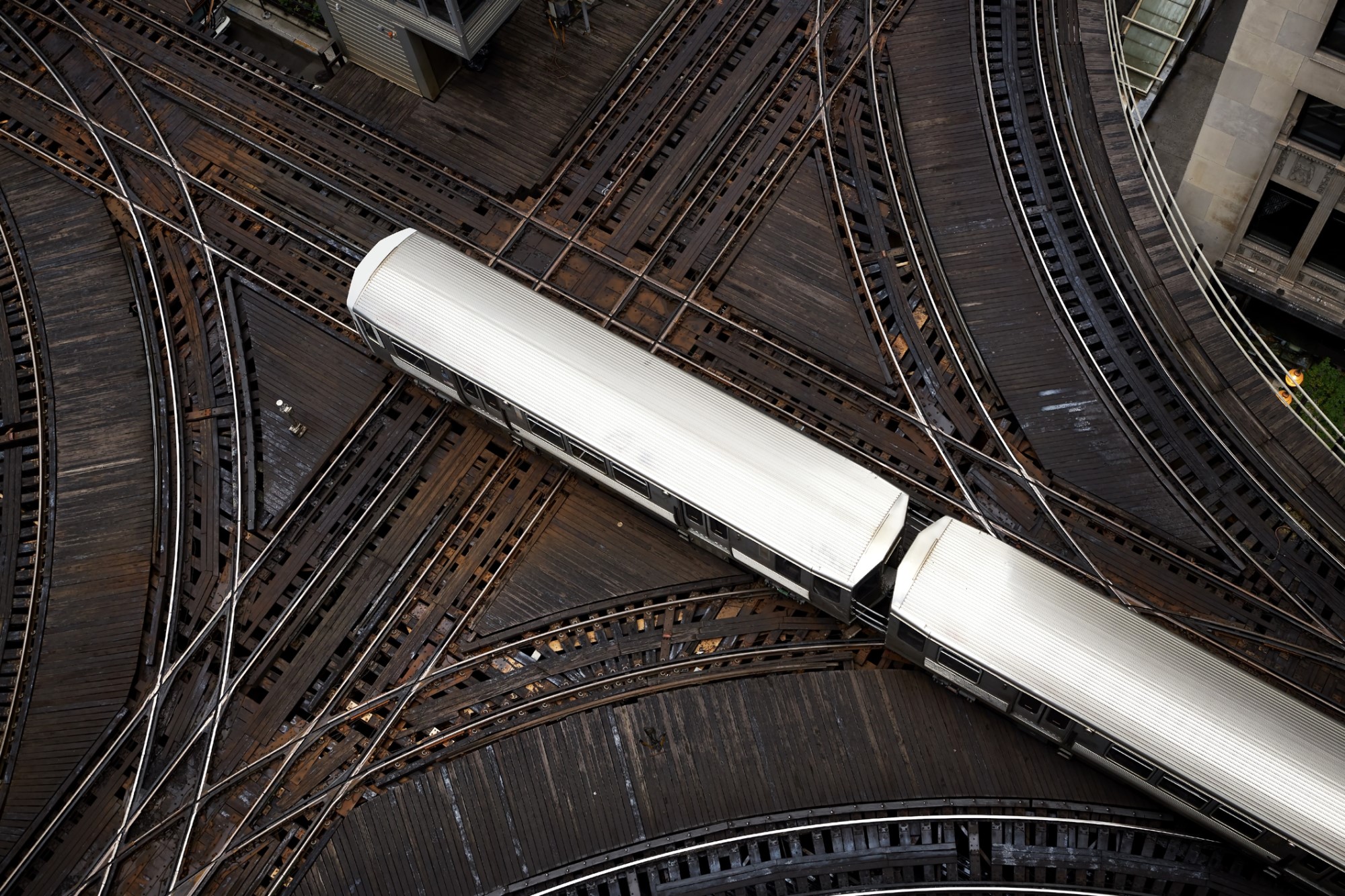

Surely one of the most popular thought experiments is the so-called “Trolley Problem”, widely discussed across American colleges as a way to introduce ethics. It actually goes back to an obscure paper written by Philippa Foot in the 1960s. Foot wondered if a surgeon could ethically kill one healthy patient in order to give her organs to five sick patients, and thus save their life. Then, she wondered whether the driver of a trolley on course to run over five people could divert the trolley onto another track in which only one person would be killed.

As it happens, when presented with these questions, most people agree it is not ethical for the surgeon to kill the patient and distribute her organs thus saving the other five, but it is indeed ethical for the driver to divert the trolley, thus killing one and saving the five. Foot was intrigued what the difference would be between both cases.

She reasoned that, in the first case, the dilemma is between killing one and letting five die, whereas in the second case, the dilemma is between killing one and killing five. Foot argued that there is a big moral difference between killing and letting die. She considered negative duties (duties not to harm others) should have precedence over positive duties (duties to help others), and that is why letting five die is better than killing one.

This was a standard argument for many years, until another philosopher, Judith Jarvis Thomson, took over the discussion and considered new variants of the trolley scenario. Thomson considered a trolley going down its path about to run over five people, and the possibility of diverting it towards another track where only one person would be run over. But, in this case, the decision to do so would not come from the driver, but rather, from a bystander who pulls a lever in order to divert the trolley.

The bystander could simply do nothing, and let the five die. But, when presented with this scenario, most people believe that the bystander has the moral obligation to pull the lever. This is strange, as now, the dilemma is not between killing one and killing five, but instead, killing one and letting five die. Why can the bystander pull the lever, but the surgeon cannot kill the healthy person?

Thomson believed that the answer was to be found in the doctrine of double effect, widely discussed by Thomas Aquinas and Catholic moral philosophers. Some actions may serve an ultimately good purpose, and yet, have harmful side effects. Those actions would be morally acceptable as long as the harmful side effects are merely foreseen, but not intended. The surgeon would save the five patients by distributing the healthy person’s organs, but in so doing, he would intend the harmful effect (the death of the donor). The bystander would also save the five persons by diverting the trolley, but killing the one person on the alternate track is not an intrinsic part of the plan, and in that sense, the bystander would merely foresee, but not intend, the death of that one person.

Thomson considered another trolley scenario that seemed to support her point. Suppose the trolley is going down its path to run over five people, and it is about to go underneath a bridge. On that bridge, there is a fat man. If thrown onto the tracks, the fat man’s weight would stop the trolley, and thus save the five people. Again, this would be killing one person in order to save five. However, the fat man’s death would not only be foreseen but also intended. According to the doctrine of double effect, this action would be immoral. And indeed, when presented with this scenario, most people disapprove of throwing down the fat man.

However, Thomson herself came up with yet another trolley scenario, in which an action is widely approved by people who consider it, yet it is at odds with the doctrine of double effect. Suppose this time that the trolley is on its path to run over five people, and there is a looping track in which the fat man is now standing. If the trolley is diverted onto that track, the fat man’s body will stop the trolley, and it will prevent the trolley from making it back to the track where the five people will be run over. Most people believe that a bystander should pull the lever to divert the trolley, and thus kill the fat man to save the five.

Yet, by doing so, the fat man’s death is not merely foreseen, but intended. If the fat man were somehow able to escape from the tracks, he would not be able to save the other five. The fat man needs to die, and yet, most people do not seem to have a problem with that.

Thomson wondered why people would object to the fat man being thrown from the bridge, but would not object to running over the fat man in the looping track, when in fact, in both scenarios the doctrine of double effect is violated. To this day, this question remains unanswered.

Some philosophers have made the case that too much has been written about the Trolley Problem, and too little has been achieved with it. Some argue either that the examples are unrealistic to the point of being comical and irrelevant. Others argue that intuitions are not reliable and that moral decisions should be based on reasoned analysis, not just on feeling “right” or “wrong” when presented with scenarios.

It is true that all these scenarios are highly unrealistic and that intuitions can be wrong. The morality of actions cannot just be decided by public votes. Yet, despite all its shortcomings, the Trolley Problem remains an exciting and useful approach. It is extremely unlikely someone will ever encounter a situation where a fat man could be thrown from a bridge in order to save five people. But the thought of that situation can elicit thinking about situations with structural similarities, such as whether or not civilians can be bombed in wars, or whether or not doctors should practice euthanasia. The Trolley Problem will not provide definite answers, but it will certainly help in thinking more clearly.