Voting in the 2016 Election: Impact Versus Intent

This past election cycle has been particularly divisive. In the last week, the response to a Trump victory has sparked protests across the country. Students have walked out of classes at UC Berkeley, and as protests in major cities have been more or less continuous since election day, violence broke out in Portland, OR in the hours between Friday and Saturday morning. Chants outside Trump Tower in New York City have included “Not My President” and “Love Trumps Hate.” In Los Angeles, protestors chant in Spanish and hold signs defending the rights of immigrants and undocumented Americans, a group that has been a focal point of a great deal of divisive rhetoric of the president-elect’s campaign. Opponents of the Trump candidacy have used personal messages throughout protest, rejecting the underlying meaning of a Trump presidency more than any particular policy he might adopt.

With a great deal of rhetoric articulating the choice for president as one between the lesser of two evils, it is difficult to view the choice of voters on opposing sides in a positive light. Because Clinton is seen as untrustworthy, callous regarding the interests and needs of the majority of Americans and without an interest in fixing the corruption in Washington, voting for her could be seen as supporting such positions.

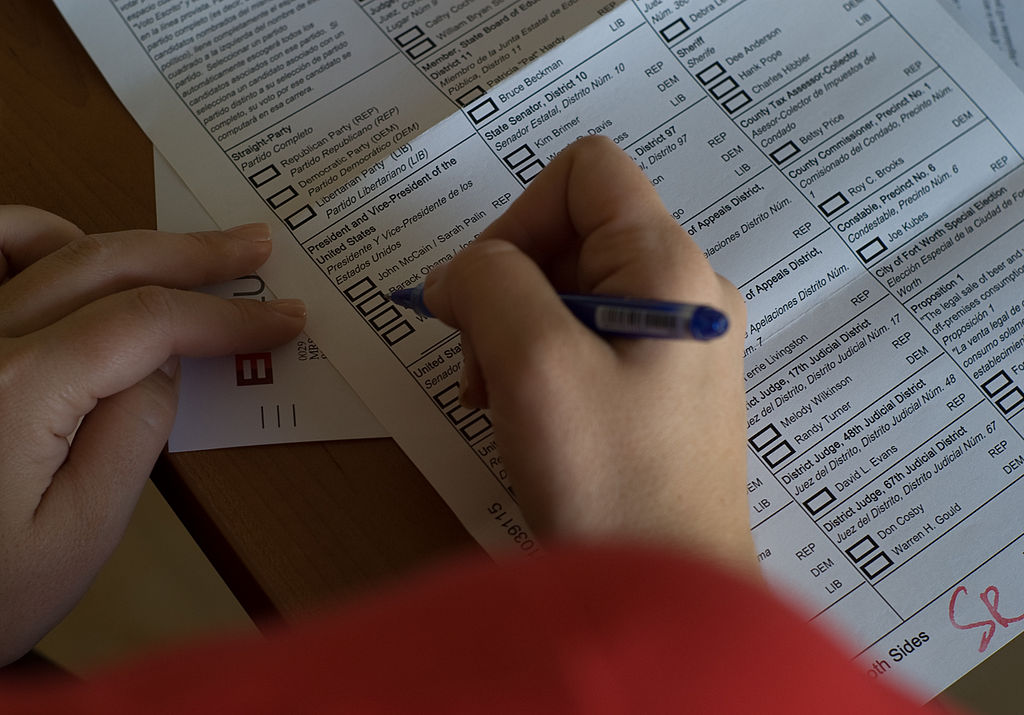

Throughout his campaign, the now-president-elect, Trump, has identified himself as a xenophobic, racist, misogynistic bully. It was one of the more shocking election outcomes in memory. Though an estimated 46.9% of the eligible population did not cast a vote (typically these data are finalized two weeks after a national election), and so in fact the 47.5% of the votes cast for Trump amounts to about 27% of the country in fact voted for Trump, does this mean that we found out last week that about a quarter of the country are xenophobic, racist, misogynistic bullies?

There are many statements on both sides of the political spectrum that defend Trump voters, claiming they are not racist, making a distinction between voting for someone with a prejudiced and oppressive worldview and endorsing such a worldview yourself. There are many reasons that individual voters chose Trump on the 8th besides endorsing his hateful rhetoric. They could have been voting “against Clinton”; they could have voted for him “despite” the hate and oppression he embodied in his campaign. In other words, the intentions of the voters could have diverged from the oppressive, discriminatory, hateful rhetoric that Trump used in his campaign.

The explicit intentions of the voters aren’t the only thing that is important, however. In ethics, there is a familiar distinction between your intention and the effect of your action.

You don’t have to have intended a harm in order to have done wrong, or to be responsible for causing the harm. In ethics, this isn’t an uncommon position to take. Consequentialists, for instance, would have no trouble agreeing with this sentiment. According to consequentialist doctrine, what is morally relevant is the result of your behavior, so if what you did leads to something bad (unhappiness, or a decrease in good characterized in some other way, depending on the particular theory), then you did the wrong thing.

Obviously, not everyone is a consequentialist, and it is a burden on any ethical theory to account for the way that our intentions do make a relevant difference to the moral quality of our behavior.

Actions can harm others despite our best intentions, however, and we can quickly get off base if we over-emphasize intent when there are real harms that need to be recognized and dealt with. This doesn’t need to be understood on a grand scale in order to be intuitive. In everyday life it can happen that, though I may have wanted to do something innocuous or even nice for someone, I may make a mistake it comes off negatively. Consider an example where a friend of mine has a hard time speaking up in company meetings. I decide to present his idea for him, thinking that the praise the idea will garner will raise his confidence to speak up next time.

In fact, the impact this has on my friend is not what I anticipated: he sees that I’ve taken an idea as my own, presented it differently than he would have, removed one of the rare opportunities he would have had to speak up, and misunderstood the systematic reasons he has for not speaking up in the first place: I identified it with insecurity over praise instead of talking to him about it. Though my intentions here are good, focusing on that is missing the more relevant aspect of this action: the impact on my friend. In order to move forward that is clearly the more important thing to address and understand.

This framework is how oppressed and marginalized individuals have emphasized understanding behavior by individuals and systems that would otherwise balk at being labeled as racist, xenophobic, misogynist, etc. (for a quick take on this distinction, see this piece). You can have good intentions, but still have an oppressive impact on the world, on individuals. It is the impact that is important to track and be aware of, and to hold yourself responsible for.

There are real impacts that are immediate in a Donald Trump presidency. Consider examples from the first week: Trump has named a white nationalist as “Chief Strategist to the President.” Because Trump has made so many promises to reduce the rights of undocumented Americans, the University of California has responded to the election by providing counselors to its students, and Janet Napolitano, the Chancellor, rushed to reassure undocumented students that she will remain inclusive and support protections against deportations. Marginalized individuals have experienced a significant spike in harassment, violence, and hate in the last week, including a “lynching thread” of group messages amongst students at the University of Pennsylvania, making it no surprise that suicide hotlines have had record high number of calls from marginalized individuals, worrying for their overall safety and well-being.

The distinction between what you intend and the impact of your action preserves the possibility of distinguishing between endorsing a candidate because of their hateful rhetoric and despite of it. There is a difference, after all, between causing a harm intentionally and unintentionally. If I sneeze while driving and collide with another car, injuring two, this is a different situation than if I, filled, with rage, ram my car into another and injure two. Noting the difference that intentions make in our actions doesn’t mean this is the end of the story, however. Having good intentions, or, like the sneeze example, lacking bad intentions, doesn’t absolve us of the hard work of trying to make things right and understanding the impact of our behavior. If we injure two people as a result of our driving, we have to take responsibility for the fall out. This may be a different fall-out than intentional assault, just like intentional racism looks different, perhaps, from negligent racism. But it doesn’t mean that people weren’t impacted by our actions, and that our relationships with them have been damaged, or at the very least changed in a way that we should attend to.

The long-term impact of voting for Trump has yet to be seen, but given the negative impact that his election has had thus far, the distinction between voter intention and the impact of this action has become particularly relevant, especially for those feeling the effects of the election directly. In ethics, the import of good intentions versus consequences has been debated continuously, and now in our nation the practical result of weighing these aspects of our behavior has taken on a new pertinence.