Three’s a Crowd: Third Parties in Presidential Debates

As the 2016 presidential election draws near, many voters will tune in to watch a series of debates between the leading candidates for the highest office in the land. The first debate, between Democratic nominee Hillary Clinton and Republican nominee Donald Trump, took place on September 26. These two major candidates have the distinction of having, respectively, the highest disapproval ratings in the history of candidates for the office.

In light of this, some very vocal American voters feel that third party candidates should be more visible to the electorate. The best way to accomplish this, they feel, is for those candidates to participate, alongside the Republican and Democratic nominees, in the televised presidential debates. Specifically, in this election cycle, there is a call to include Independent candidate Gary Johnson and Green Party candidate Jill Stein. In nationwide polls, Johnson averages 9% and Stein averages 3%.

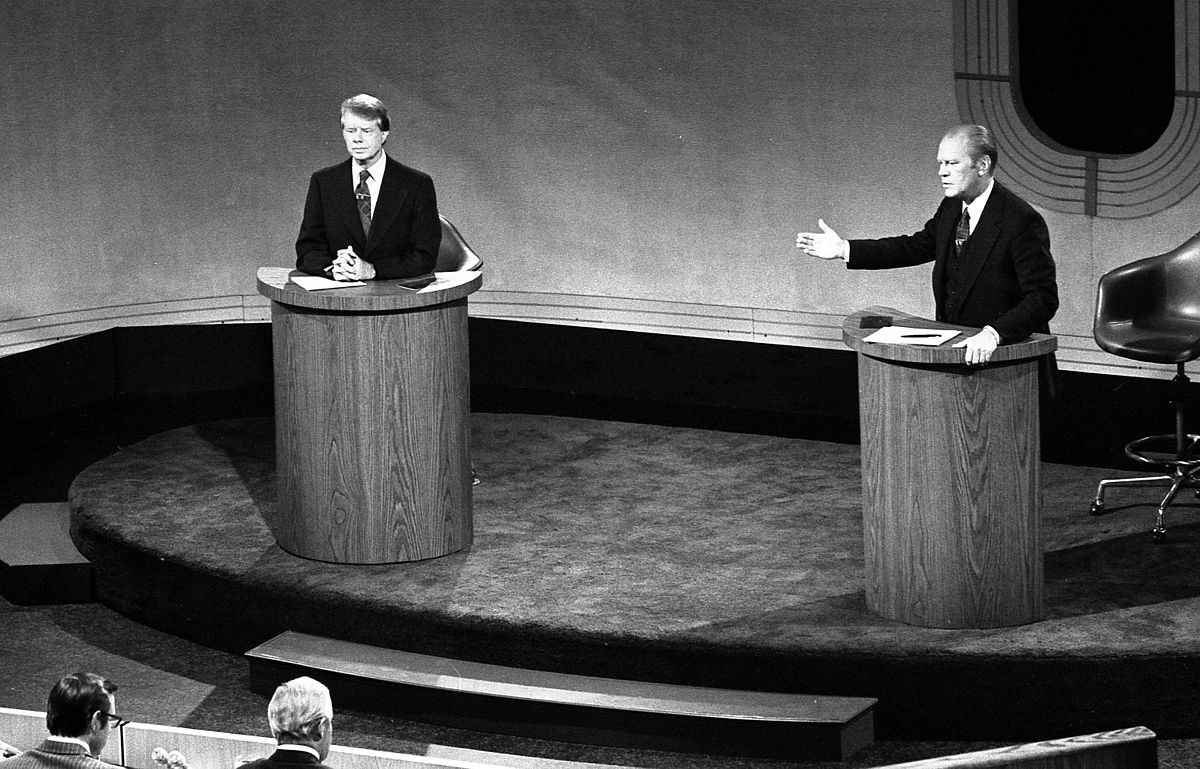

Though presidential debates did take place, they were rare before 1976, when The League of Women Voters (LWV) began sponsoring and running them routinely. As a neutral third party interested in educating the voting public, the LWV ran the debates from 1976 to 1988. In 1988, insiders from both the Republican and Democratic parties met independently, without the knowledge or participation of the LWV, relegating the role of the LWV to a merely organizational one. In response, the LWV withdrew their sponsorship of the debates. In a memorandum issued for release to news agencies on October 3rd, 1988, LWV President Nancy M. Neuman said, “It has become clear to us that the candidates’ organizations aim to add debates to their list of campaign-trail charades devoid of substance, spontaneity and honest answers to tough questions. The League has no intention of becoming an accessory to the hoodwinking of the American public.” Since that time, many citizens have felt that the presidential debates are no longer conducted with the aim of educating the citizenry in mind.

Since 1988, The Commission on Presidential Debates (CPD) has been responsible for organizing the events. The commission is registered as a 501(c)(3) organization. This means that it is not-for-profit and is not funded by any candidate, political party, or political action committees. The commission does receive donations from corporate, foundation, and private donors. Donors have no input on commission guidelines or on who gets to participate in the debates.

Many candidates run for President every election cycle. It is necessary, therefore, for the CPD to establish some guidelines to determine who gets to participate in the debates. The guidelines for 2016, are the following: 1) the candidates must be constitutionally eligible for the office, 2) the candidates must appear on enough state ballots for it to be mathematically possible for them to win the electoral college, 3) They must have an average of 15% support nationally, determined by five polls selected based on their methodological integrity. This year, the polls identified were ABC-Washington Post, CBS-New York Times, CNN-Opinion Research Corporation, Fox News, and NBC-Wall Street Journal.

It is worth noting that the regulations of the CPD have not always, in practice, ruled out third party candidates. For example, Independent candidate Ross Perot participated in all three debates in the 1992 election against Bill Clinton and incumbent president George H.W. Bush. At this point, however, candidates were not required to average 15% in the polls.

The CPD is tasked with making sure that the debates take place each election cycle. No candidate has ever been required to participate. Before the CPD took over, it was not uncommon for candidates to decline to participate. For example, Lyndon Johnson declined to debate in 1964, and Nixon did the same in 1968. Supporters of the CPD’s guidelines point out that the guidelines raise the probability that the debates will actually occur. After all, allowing third party candidates with reasonably low poll numbers to participate is not in the best interests of the most popular candidates. The participation of third parties is unlikely to do anything but cut into their poll numbers. It would be wise, then, for them to decline to participate in debates that include candidates with substantially lower poll numbers. Since it is in the best interest of the citizenry for the debates to occur, it would follow that the guidelines are also in the best interest of the citizenry.

Supporters of the guidelines point out that it is not practical to simply allow anyone who decides to run for the presidency to participate in the debates. There must be some point at which the support for the candidate is too insignificant. The debates last 90 minutes. Guideline supporters argue that this time is best spent allowing the moderator to press candidates who actually have a chance of winning on their positions. It is also important to afford the prominent candidates a chance to criticize one another’s positions. If third party candidates are allowed to participate regardless of their poll numbers, the debates might not highlight the strengths and weaknesses of the candidates as effectively as they would have otherwise.

Many opponents of the guidelines argue that the current, two party system is deeply problematic, especially when those parties cast themselves against one another at the expense of legislative progress. Third parties have no chance of rising to prominence and challenging the current system unless they have more public visibility. With 80 million viewers, the September 26, 2016 debate set a new viewership record for presidential debates. Opponents suggest that third parties can never compete in the political arena without access to the same staggering viewership. If they are granted access, however, political revolution may be possible—there may be real, substantive positive change in the country.

Opponents also argue that poll numbers do not reflect the strength of ideas. After all, as illustrated by Republican and Democratic poll numbers, diametrically opposed views can fair roughly equally in the polls. Perhaps there are better ideas out there than the ones being expressed by the major political candidates, but the citizenry is being systematically prevented from hearing them.