This & That: Assisting Evolution

In a recent piece entitled Unnatural Selection published in the New Yorker, Elizabeth Kolbert writes of the challenges confronting conservation as the world moves into a new, warmer, more acidic equilibrium as a result of human-induced climate change. In her piece, Kolbert profiles two ongoing efforts to genetically-modify wild species for the purpose of regenerating natural populations. Should humans assist evolution in an attempt to fix the detrimental effects of climate change?

Connor McAndrew: Assisted Evolution Our Only Option

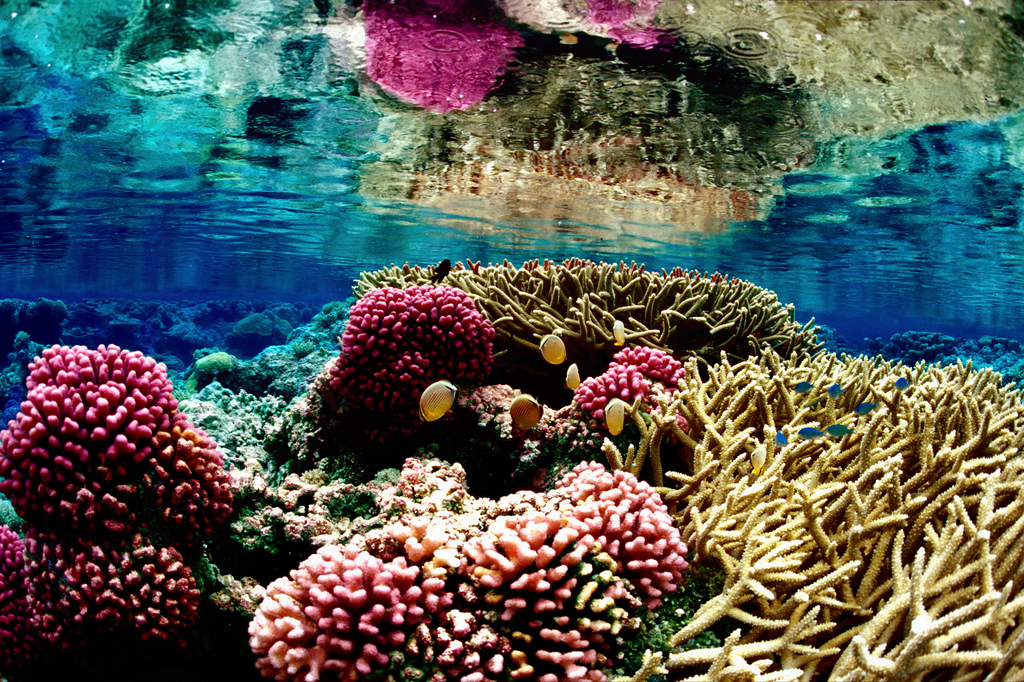

The piece focuses on two potential solutions. The first attempt, currently in development in Hawaii, aims to use helicopters and other means of mass dispersal to deposit genetically resistant polyps on top of dying coral reefs. The polyps to be dispersed are a naturally occurring genotype that can survive in the increasingly acidic, warm water expected in the 21st century that has wrought such havoc on current populations. The second, currently in development, seeks to repopulate the United States with a genetically-modified species of the American Chestnut tree, which was devastated by an invasive fungus over the course of the last century.

These efforts have met a mixed reception. That is justified. Genetic modification for the purpose of agriculture is an accepted, albeit controversial, part of humanity’s current food production scheme. However, these plants are generally restricted to certain plots of land, and their reproduction is monitored and/or inhibited.

Introducing genetically modified plants to the wild would be entirely different. No such constraints on reproduction, dispersal, or mutation exist in the wild, and, as such, it is impossible to overstate the risk of rampant population growth. It is impossible to entirely understand the effect a new, modified species may have on an ecosystem and biodiversity.

That being said, I believe that genetically-modified organisms for the purpose of conservation hold the most promise for protecting and preserving our natural world. If the current status quo holds true, we, as humans, can expect an increasingly barren world in which human demand and capitalism continue to decimate biodiversity as a result of overfishing, growing greenhouse emissions and deforestation.

Natural species that evolved in a pre-anthropogenic era will not, as a vague rule of thumb, adapt rapidly enough to survive at this new human-induced equilibrium point. Even if the death of a species is a result of a natural phenomenon — a fungus, in the case of the chestnut — science and technology offer the opportunity to save species that would otherwise fade into extinction.

Is this a catch-all solution? Clearly not. However, in the case of ecologically essential populations like coral reefs, which provide global benefit through their carbon dioxide-scrubbing abilities, it offers humans another tool in mitigating climate change.

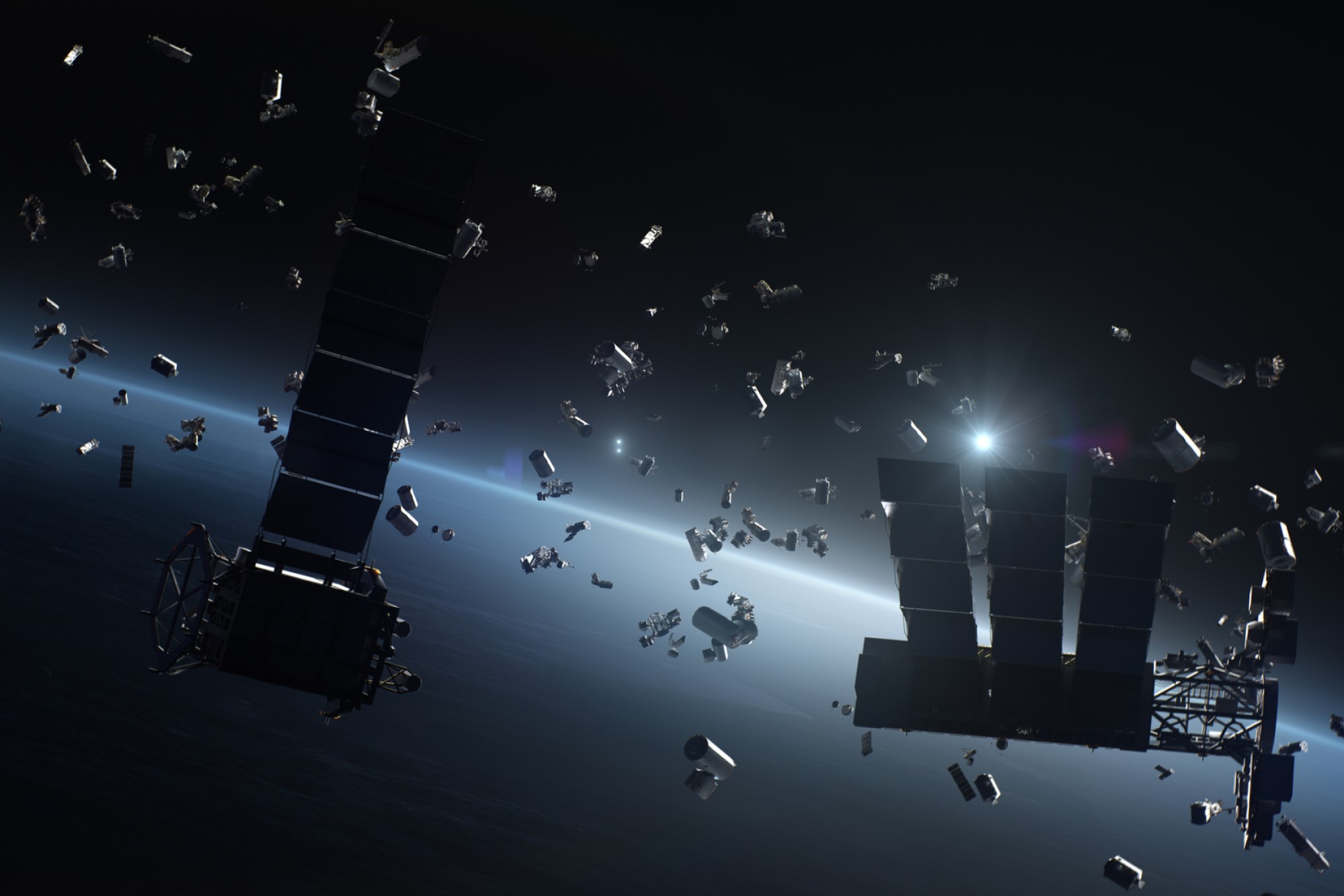

In a perfect world, human growth would be checked by a global hegemonic organization that has the power and legitimacy to drive sustainable, clean growth at low emission levels that capitalizes on developed land and resources without infringing on the natural world. This is a pipe dream.

Reality is far different. It is not rational to expect humanity to stop releasing carbon into the atmosphere or stop demanding new resources. National efforts may mitigate the effects of climate change, but they will not change the basic nature of human beings.

As such, we must use the technology that has proved so effective in destroying the environment to save it.

Amy Brown: Super-Corals Not a Magic Solution

While the intentions of creating super-corals or genetically modified chestnut trees are well-meaning, the issue with assisting evolution is that it sets a dangerous precedent. Humans have messed up numerous aspects of the environment, and there are plenty of species that are dying out because of climate change caused by humans. By focusing on fixing the effects of the problem, we are not truly getting at the root of the problem. While saving species from dying out is positive, if we rely too heavily on programs that aim to save a species and not on preventing it from happening again in the future, we do not change the dangerous behavior that caused the situation. Turning toward programs that seek to quickly evolve species to adapt to the new climate will shift the focus away from prevention and conservation and toward quick-fix solutions that might not be plausible.

These programs sound great, but it appears that they are incredibly costly. Two hundred and fifty projects combined cost a quarter of a billion dollars and only covered the area of two football fields. The cost of the projects, and the fact that it appears that it will be incredibly difficult to truly incorporate the assisted species over any sizable portion of land or sea for it to truly be effective, makes these projects seem implausible. While the idea that we can reverse the detrimental effects humans have had is a good idea, these projects are not the solutions they are being marketed as. Distribution of such species, specifically the ‘super-coral’ that is being attempted, may take hundreds or thousands of years to work and spread naturally. Distribution methods of such projects and production would have to speed up. Additionally, the climate will continue to change during that period, perhaps to the point where these species are not evolved enough to handle it.

Biologists have also warned against these projects – tampering with the Earth and evolution could end up doing more harm than good. The modified species could take over other species and eliminate biodiversity – one of the consequences that we are trying to prevent in the first place. It’s impossible to know exactly how these species would truly affect the environment, biodiversity, and the planet long-term. It’s best to focus on conservation and do more on that end of the issue, rather than try to create a genetically engineered or human-assisted evolutionary solution. Potentially, they could be part of the solution when they get further developed and researched, but not the entire solution.