The Future of Cryogenic Preservation

No parent ever wants to outlive their child, especially when a young life is cut tragically short by a horrible disease. What if there was a way to freeze time until scientists found a cure for this disease, giving the child a second chance?

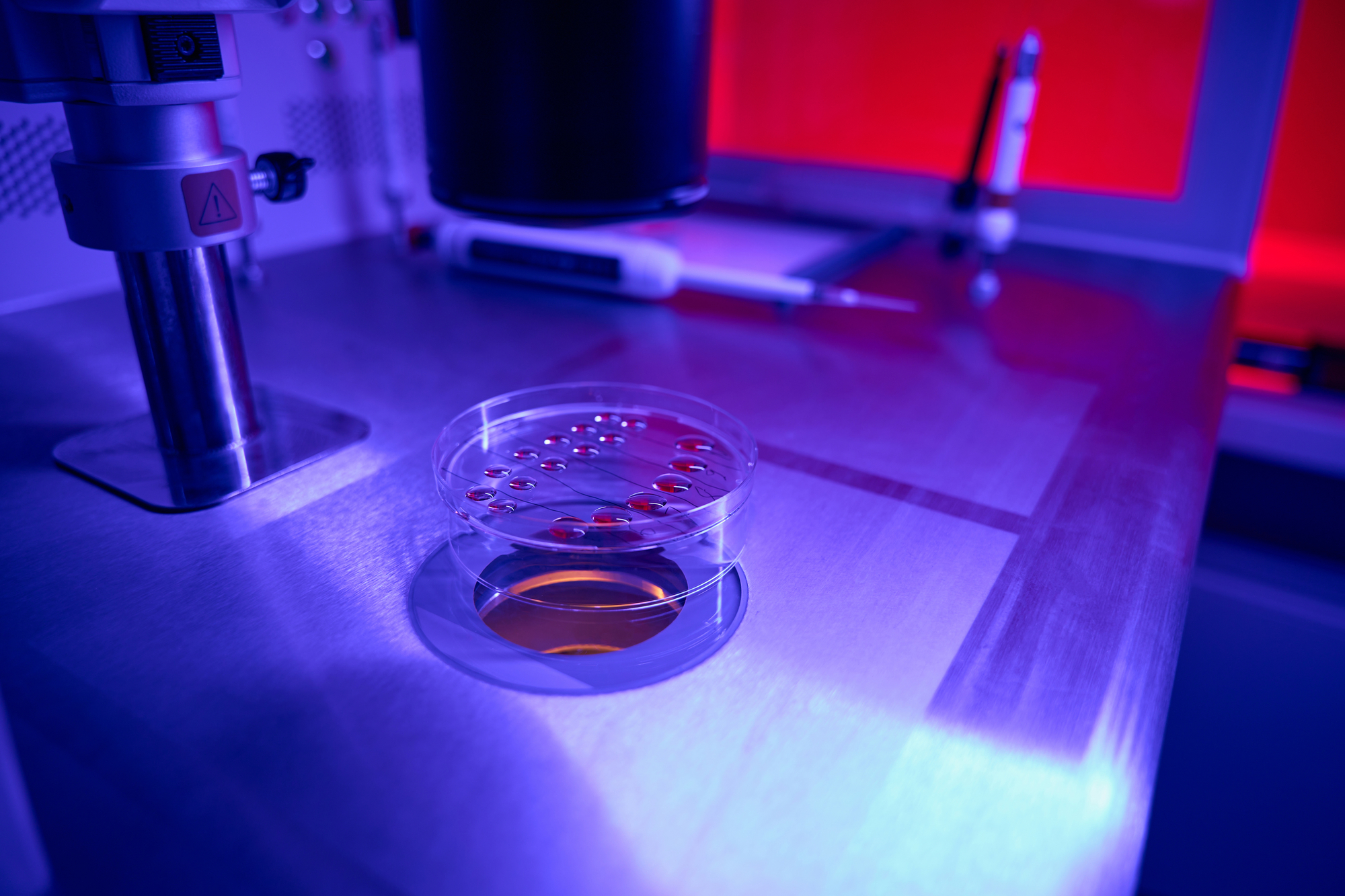

In essence, this is what a set of parents in Thailand are hoping for their two year old daughter, nicknamed Einz. Einz was diagnosed with brain cancer just after her second birthday and passed away just before her third birthday. Her parents, both medical engineers, made the decision to utilize the technology of cryonics to freeze Einz’s brain moments after her death and have it stored at an Alcor facility in Arizona. The hope that Einz’s parents have is that one far-off day, extraordinary advances in medical technology will allow her brain to be reanimated, and for a new body to be created for her, giving Einz a second chance at life.

As someone who experienced first-hand the ways in which medical technology such as in vitro fertilization and surrogacy assisted her in birthing four children, Einz’s mother strongly believes that medical technology will also allow her daughter to live once again in the future, however long it takes for such technology to be developed. However, this story and other uses of “life-extension” services raise particular ethical issues to be considered.

Medical advances have over time made it possible for people to live longer despite the plethora of illnesses that exist, but does there become a point when “overcoming death,” as stated by Einz’s father, goes too far in violating the natural course of life and physics? Do we risk too much of a dependence on medical technology and science in our lives? Further, are we willing to accept the consequences if this future technology is not successful and the results of trying to reanimate cryogenically frozen brains are gruesome and even more harmful to the already deceased brains?

Additionally, although Einz is not the first person to ever have her brain cryogenically frozen, at two years old, she is by far the youngest. At this young age, Einz was not old enough to be able to make informed decisions about what would happen to her body and brain after her death, nor was she old enough to be able to consent to the choices her parents had made on her behalf. Given the specifics of this situation, is it ethical for parents to make this very serious decision about their child’s potential future revival and re-birth if this type of technology ever becomes feasible?

Parents are clearly allowed to make choices regarding cremation, funeral services, etc. about their children, but “life-extension” services are rarely a part of this equation. Einz’s parents, like many others who are increasingly turning to the hope of revival from cryogenic freezing in the future, remain optimistic about the prospect of a second chance at life, despite the potential societal consequences this technology could entail as well.