Facebook’s Online Redlining

There are many things you may share with friends on Facebook. Photos from parties or long conversations on statuses, perhaps. The same goes for content like memes and shareable videos calling the viewer to action on some cause. One thing you may not share, though? Your credit score.

Soon, however, even this typically private data may change. According to a report by Venturebeat, Facebook recently filed a patent for a service that “tracks the way users are connected in a network.” The primary use of the service, the patent says, would help cut down on spam and other social media nuisances. However, Facebook’s patent also described how lenders could use the service when screening loan applicants. The service, the patent argues, could allow these lenders to check the credit ratings of the people in the individual’s social network, using this information to approve or deny the individual’s loan application accordingly.

At first glance, such a program would seem in line with the overlap of professional life and social media. After all, employers already screen applicants’ social media accounts before making hiring decisions. However, this appears to be an entirely different issue than acts of speech on social media. The consequences of such actions are still being debated, as dozens of people have been fired from their jobs for making controversial social media posts. Such practices have driven controversy about online justice in recent months, raising questions about the ethics of “doxxing” and crowdsourcing justice.Yet this practice is different; merely by nature of proximity or connection to a person with poor credit, lenders using Facebook’s tool could decline an individual’s loan.

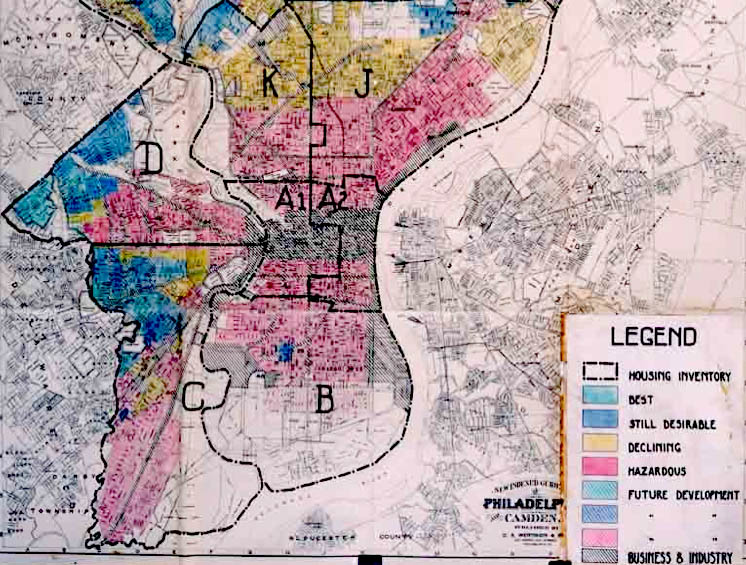

While this practice may make practical sense for lenders, its seemingly problematic design sparks fears of past discrimination. In particular, the process seems eerily reminiscent of a practice known as “redlining,” a process used by the Federal Housing Authority (FHA) throughout the mid-twentieth century. Named for the color-coded municipal maps that it produced, the process categorized entire neighborhoods as no-loan zones. Many of the neighborhoods affected were disproportionately populated by low-income, non-white communities, a trend that led the FHA to ban its use in 1968. Nevertheless, some argue that “redlining” still exists, and continues to affect communities of color in the United States.

In light of practices like “redlining,” Facebook’s choice to enable loan rejection based on social connections seems particularly suspect. Discriminating based on one’s social media friends seems particularly similar to geographical “redlining,” and in many ways the two may overlap. In fact, it is possible that the two problems could feed into each other in a self-perpetuating cycle. Since regularly paying off a loan helps establish a strong line of credit, people who have been systematically denied such loans may find it more difficult to improve their credit score. When this information is picked up by Facebook’s tool, the results would leave lenders even less likely to approve loans to individuals in that community. Doing so would ultimately exacerbate issues tangential to “redlining” in affected communities, creating a damaging cycle that unjustly obstructs access to financial options.

Perhaps, then, credit rating data lies among the information that should not be shareable on Facebook. Making such data available to lenders certainly offers incentives to banks, but at a damaging and discriminatory cost for loan-seekers. Given the racially charged and discriminatory history of loans in general, this cost seems particularly unethical. It is clear, then, that Facebook must avoid enshrining discriminatory options for the loan provider, and instead protect the private data of the loan-seeker.